The End of Innocence: How the Global Economy Changed Forever (2000-2025)

The 'Goldilocks' era is over. Explore the profound economic paradigm shift from 2000-2025, driven by debt, deglobalization, and the AI race. Discover why low interest rates and stable growth are relics of the past.

|  |  |  |

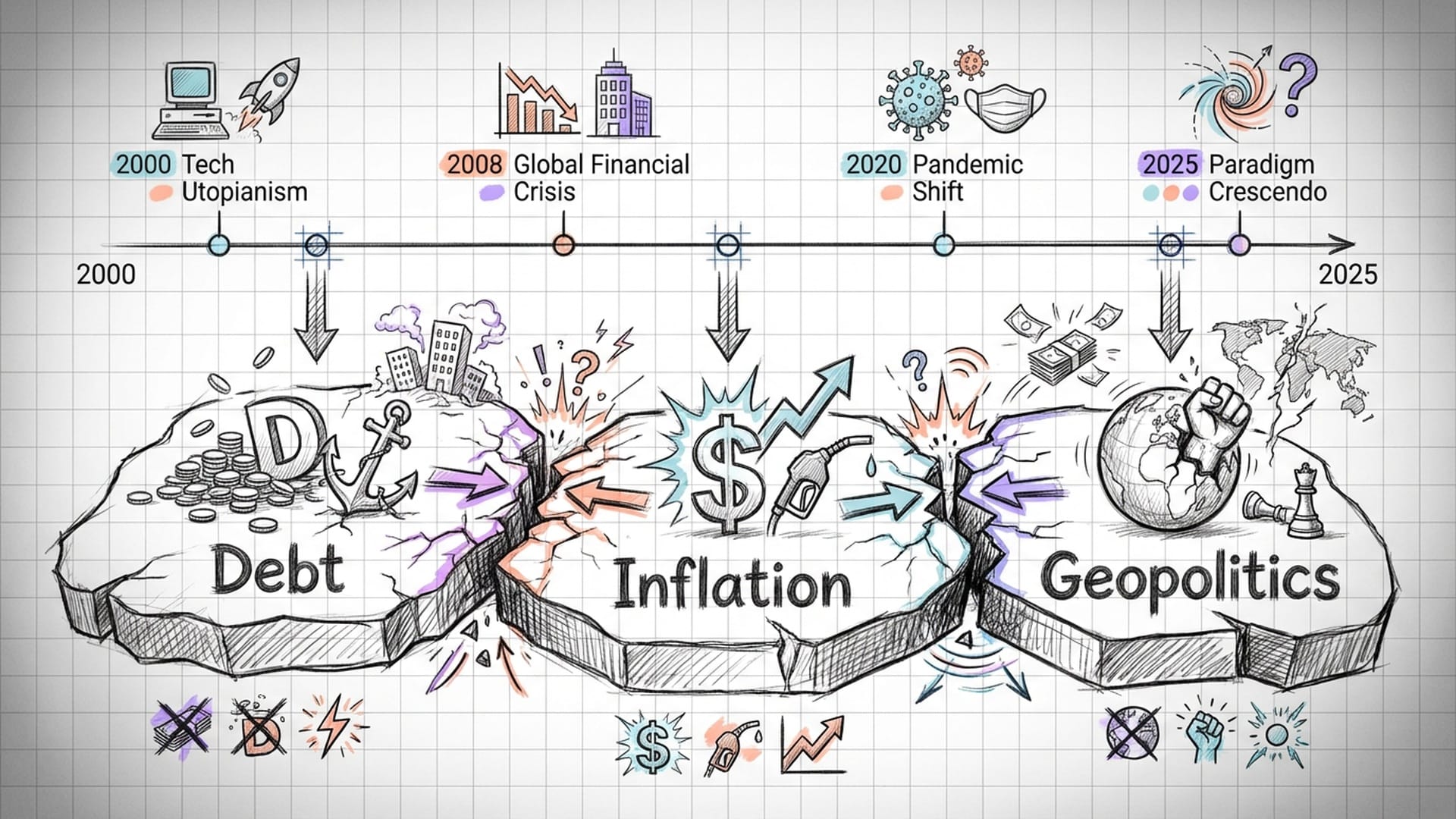

The age of economic innocence, characterized by Goldilocks conditions—low inflation, low interest rates, and low volatility—has definitively ended. We are witnessing a profound economic paradigm shift that began at the turn of the millennium and is reaching its peak in 2025. Over the past quarter-century, global economies have navigated through a series of seismic changes, shattering old certainties and forging a new, volatile reality.

Gone are the days of naive optimism from the early 2000s, the end of history delusion, and the deceptive calm of the Great Moderation. We have collectively endured the abyss of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, weathered balance sheet recessions and secular stagnation, and are now contending with the radical fiscal experiments of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic and the stunning return of inflation. The fundamental operating logic of the global economy has undergone a significant transformation.

This is not merely just a recounting of historical events; it is a structural autopsy of the forces that have reshaped the global economic landscape, with a keen focus on the economic superpowers of the U.S. and Europe. Over these twenty-five years, several titanic forces have battled for dominance:

- The monstrous expansion of the

debt supercycleand the violent reversal of interest rates. - The fading glow of globalization and the rise of

geoeconomic fragmentation. - The fierce tug-of-war between

capital and laborfor a share of the income pie. - The almost mythical hope that technological advancements, especially

artificial intelligence, can rescue us from sluggish productivity growth.

The year 2025 marks a demarcation line—the official acknowledgment of the demise of the Goldilocks era. The U.S. is currently grappling with soaring interest payments that threaten to consume its fiscal space. Europe is managing a precarious balancing act between deeper integration and the centrifugal forces unleashed by Brexit. Meanwhile, Artificial Intelligence (AI), the undisputed superstar of our current tech cycle, is striving to re-engineer the productivity curve against the relentless headwinds of an aging global population.

The Dawn of a New Millennium and the Roots of Instability

Let's rewind to the dawn of the 21st century. The year 2000 was marked by tech utopianism. The much-hyped Y2K bug, a fleeting digital bogeyman, came and went without triggering an apocalypse. Instead, it spurred a massive and much-needed upgrade of IT infrastructure. However, this veneer of technological calm masked deep structural imbalances, inadvertently setting the stage for future economic cataclysms.

The internet bubble burst in early 2000, plunging the U.S. economy into a brief but sharp recession. In response, the Federal Reserve, fearing asset price deflation, dramatically slashed interest rates, reaching a historic low of 1 percent by 2003. This policy decision inadvertently opened Pandora's Box.

"The Federal Reserve's decision to slash interest rates to 1 percent in 2003, post-dot-com bubble, was not just a policy move; it was the accidental opening of Pandora's Box, unleashing a torrent of cheap credit that would fundamentally alter the global financial landscape."

Credit surged, and vast rivers of liquidity flowed into the housing market. Economists at the time labeled this period the Great Moderation, characterized by gentle inflation and stable growth. Yet, this apparent stability was built on quicksand. Financial deregulation, notably the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, permitted the merger of commercial and investment banks, leading to the creation of complex, often opaque, Frankenstein-like derivative markets.

Simultaneously, the Global Savings Glut emerged as massive savings from rapidly growing Asian economies and oil exporters flooded into the U.S. financial system, further depressing long-term interest rates. Easy money became ubiquitous.

One of the most significant global events of this era, which continues to shape our world, was China's entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. Academic research, notably from scholars like Mary Amiti, clearly demonstrates the massive downward pressure this exerted on U.S. prices. China's lower tariffs enhanced the productivity of its companies, driving down costs. The elimination of U.S. tariff uncertainty led to a torrent of low-cost Chinese goods entering the American market.

The quantification of this impact is staggering: between 2000 and 2006, over 65 percent of the decline in the U.S. manufacturing price index could be attributed to the tariff reduction effects of China's WTO entry. This was not merely a supply shock; it was a positive supply shock that directly lowered consumer prices. Crucially, it also reduced the cost of intermediate and capital goods for U.S. businesses, artificially boosting profit margins.

Suddenly, cheap imports and cheap money became the twin pillars of prosperity. However, this imported deflation masked a dangerous truth in developed nations: concurrently rising labor costs and slowing productivity growth at home. Central bankers, fixated on low inflation numbers, mistakenly believed the economy could sustain low interest rates indefinitely without overheating. This was a critical misjudgment.

The Great Financial Crisis and Secular Stagnation

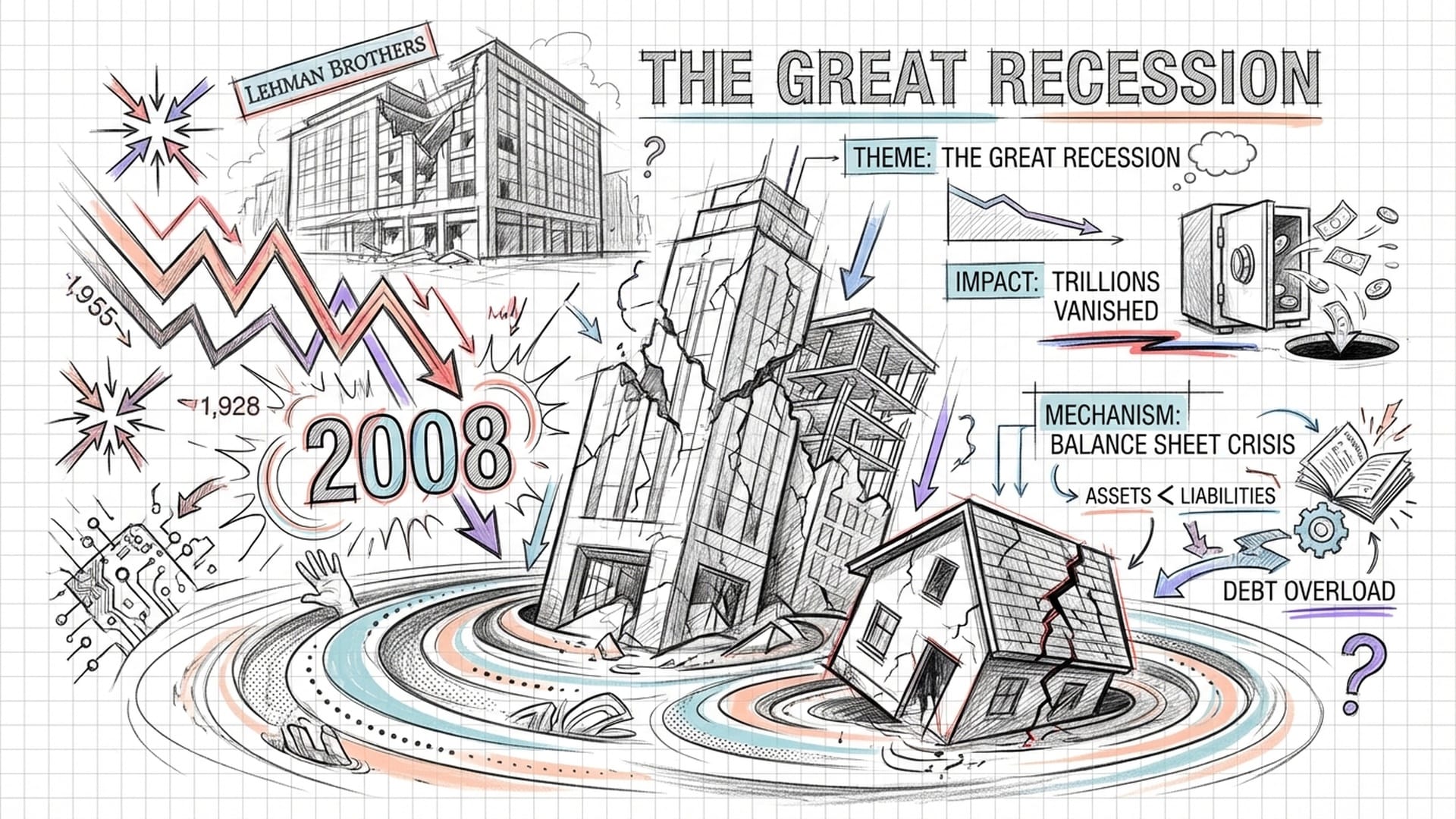

The illusion shattered with the subprime mortgage crisis in 2007. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) was no ordinary recession; it was the most severe economic disaster since the Great Depression. Trillions of dollars vanished overnight, fundamentally shattering the prevailing macroeconomic policy consensus.

The ensuing decade, often referred to as the Lost Decade or the era of Secular Stagnation, was defined by brutal deleveraging in the private sector and a painfully slow, often inadequate, public policy response. This was fundamentally a balance sheet recession.

Housing bubbles burst, wiping out trillions in household and financial institution assets. Debts, however, remained at their nominal value, leaving households and businesses underwater. Their primary objective shifted from profit maximization to debt minimization. Even with interest rates slashed to zero, demand for borrowing evaporated, creating a classic liquidity trap. The recovery was excruciatingly slow.

"The 2008 Global Financial Crisis wasn't just a downturn; it was a profound reset. It revealed the inherent fragility of a system built on cheap money and overlooked structural imbalances, ushering in a 'balance sheet recession' where conventional monetary tools proved insufficient."

Research from the Federal Reserve and NBER indicates that from 2000 to 2010, real household income for all income groups in the U.S. declined—a phenomenon rarely observed since World War Two.

Policy Missteps and the Decline of R-Star

In the immediate aftermath of the crisis, policymakers were constrained by what Jason Furman termed the old view of fiscal policy. This mindset advocated for short-lived, limited fiscal stimulus, with monetary policy primarily responsible for managing economic cycles. A pervasive fear of accumulating public debt further hampered decisive action. This intellectual dogma led to catastrophic policy errors.

In the U.S., the massive 2009 Recovery and Reinvestment Act was quickly followed by fiscal consolidation after 2011. Europe fared even worse. Amidst the sovereign debt crisis, core nations, led by Germany, aggressively pursued austerity. Southern European countries plunged into a deflationary recession that persisted for years.

Because fiscal policy retreated too early, the entire burden of recovery fell on central banks. The Federal Reserve embarked on three rounds of Quantitative Easing, maintaining near-zero interest rates for seven long years. However, monetary policy has inherent limits in a balance sheet recession. While it can inflate asset prices, it struggles to translate into real credit growth for the economy or wage growth for workers.

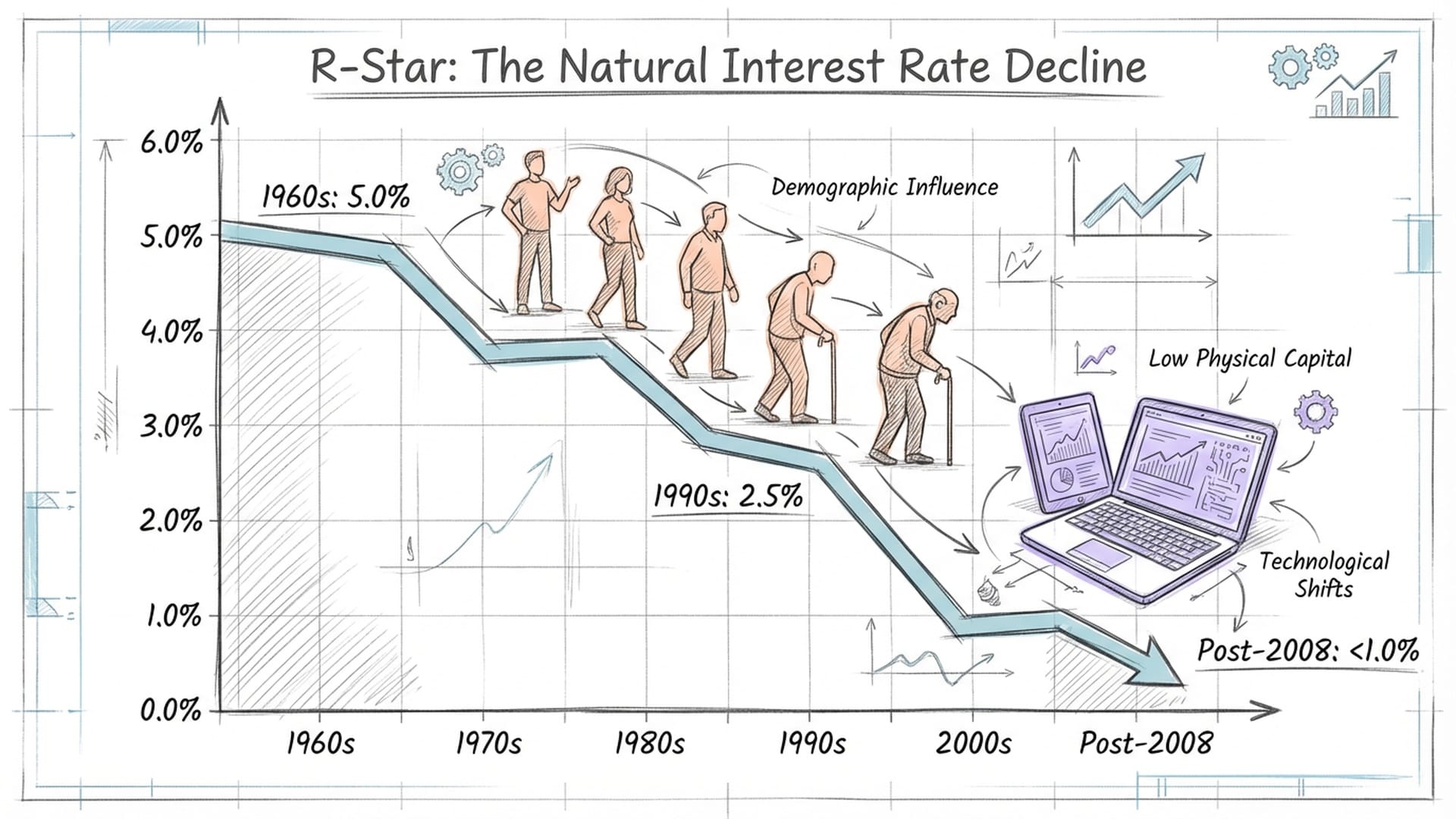

A striking macroeconomic phenomenon of this period was the structural decline of the natural interest rate, or R-star. Estimates from the Holston, Laubach, and Williams model show R-star plummeting from approximately 5 percent in the 1960s to near zero post-2008, remaining below 1 percent for the subsequent decade. This decline was structural, not merely cyclical.

Several factors contributed to this:

- Demographics: The

Baby Boomersentered their peak saving years, contributing to a global savings glut. - Productivity Growth: The fruits of the third technological revolution began to diminish.

- Investment Demand: The digital economy required less physical capital, and the falling relative price of capital goods further reduced the need for investment.

This low-interest-rate environment eased government debt servicing costs but also distorted asset prices, exacerbated wealth inequality, and left central banks with a daunting question: what more could they do when rates were already at zero?

The Post-Pandemic Regime Change

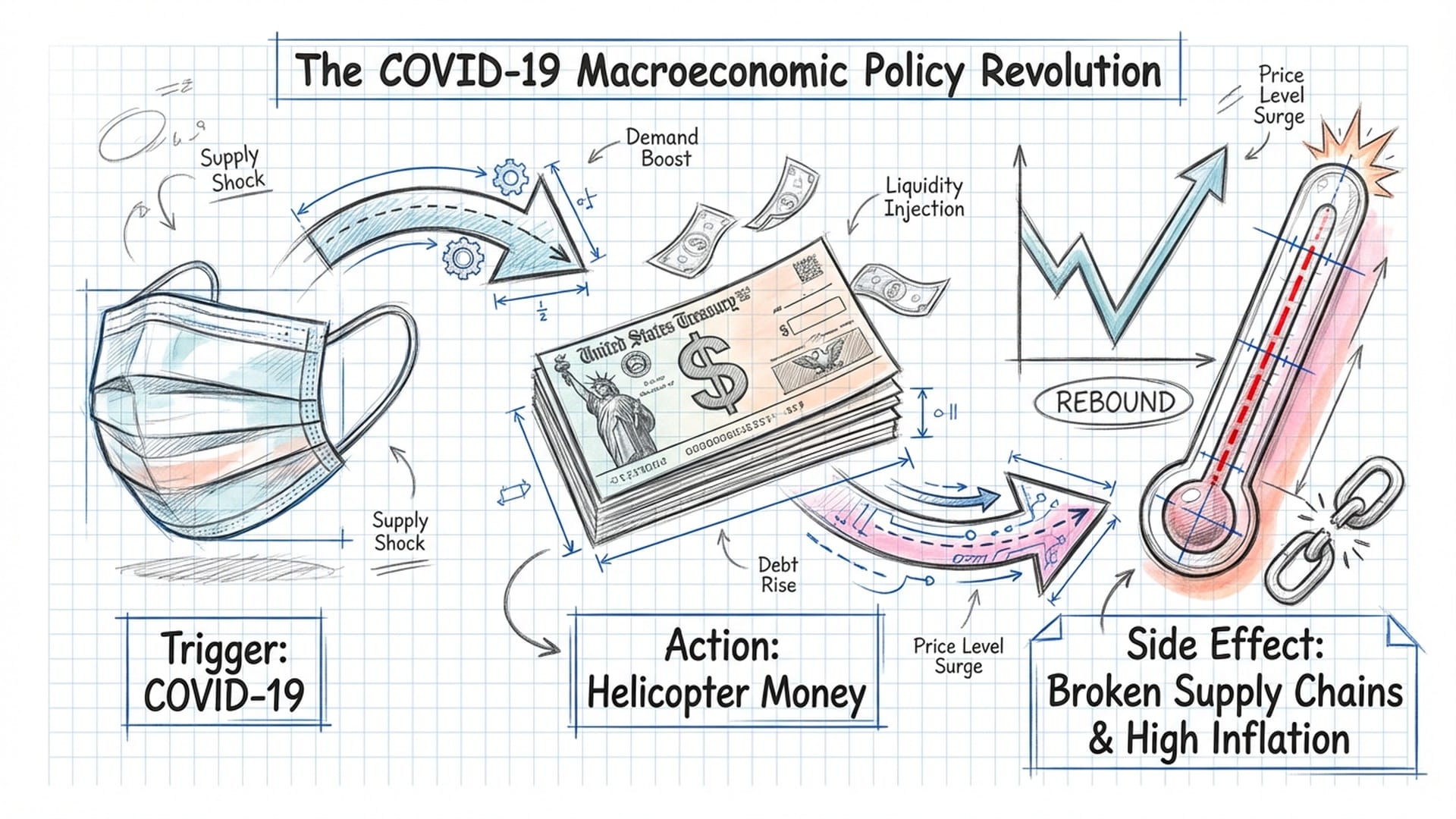

Then came 2020 and the COVID-19 pandemic. This was more than a public health crisis; it was a macroeconomic policy revolution. It effectively ended the secular stagnation narrative and ushered in a dramatic new era of high inflation, high deficits, and high interest rates—a true regime change.

Faced with an unprecedented external shock, policymakers swiftly abandoned the old dogmas of 2008. They embraced Jason Furman’s new view of fiscal policy, which posited that in a low-interest-rate environment, fiscal policy should take the lead. Stimulus should be aggressive and even oversized, without excessive concern for moral hazard or short-term debt levels.

The U.S. government unleashed massive fiscal relief packages between 2020 and 2021, with federal spending skyrocketing by roughly 50 percent in just two years. This helicopter money approach, involving direct transfers to households, successfully shored up household balance sheets and fueled a V-shaped economic rebound.

However, this aggressive demand-side stimulus collided head-on with severe supply-side constraints, including broken supply chains and plummeting labor force participation. The inevitable result: inflation came roaring back with a vengeance.

As inflation soared, the Federal Reserve in 2022 initiated the most aggressive interest rate hiking cycle in decades. For the Treasury, this meant an explosion in debt interest costs. The seemingly magical era of debt increasing but interest costs falling (2000-2020) was over. Now, both the debt stock and interest rate levels were rising simultaneously, creating a grim new reality.

By fiscal year 2025, the U.S. federal deficit reached 1.78 trillion dollars. Even more alarming is the pace of interest spending growth. In the first two months of fiscal year 2026, interest payments were 11.9 percent higher than the previous year. The Peter G. Peterson Foundation reports that interest costs have become the federal government's second-largest expenditure item, surpassing defense and Medicare spending, and trailing only social security.

This interest burden is incredibly sticky. With vast volumes of low-interest Treasury bonds maturing and requiring refinancing at much higher rates, the overall weighted average interest rate on debt will continue to rise, even if the Federal Reserve begins cutting rates in 2025. This situation not only squeezes out space for productive investment but also raises serious concerns about the long-term fiscal sustainability of the United States.

Inequality: Wealth vs. Wages

Over these 25 years, inequality has remained a central theme in global economic discourse. However, detailed data analysis reveals a seemingly contradictory yet deeply significant phenomenon: the relentless worsening of wealth inequality coexisting with a recent, unexpected reversal in wage inequality.

Wealth concentration in the U.S. has been an unwavering trend. According to the Federal Reserve, the share of national net wealth held by the richest 1 percent of Americans climbed steadily from 22.8 percent in 1989 to an astounding 30.8 percent by 2024, controlling approximately 49.2 trillion dollars. In stark contrast, the wealth share of the bottom 50 percent of households shrunk from 3.5 percent to a mere 2.8 percent.

This divergence is largely driven by asset price inflation. Wealthy households own the vast majority of stocks and real estate, so the low-interest-rate environment from 2000-2021 directly inflated their balance sheets. After the 2008 financial crisis, while housing prices initially plunged, narrowing the wealth gap momentarily, the subsequent recovery was intensely K-shaped—the stock market rebounded quickly, while real estate, crucial for the middle class, recovered far more slowly. The racial wealth gap also remains deeply ingrained, largely due to historical discrimination and intergenerational wealth transfers.

On the other hand, a quiet revolution took place in income (a flow) between 2019 and 2024. During this period, the U.S. labor market experienced The Great Compression, where the wages of low-income workers grew significantly faster than those of high-income workers. Research by scholars like David Autor and Arindrajit Dube highlights that in the post-pandemic labor market recovery, severe labor shortages dramatically increased the bargaining power of low-wage service workers. This led to wage growth for the 10th percentile (low income) significantly outpacing the 90th percentile (high income), offsetting about 40 percent of the accumulated wage inequality increase over the past four decades.

This trend was driven by:

- A

tight labor marketwith consistently high job vacancies. - Proactive

state minimum wage increases. - A shift in social norms re-evaluating

essential workers.

Despite this, persistently high inflation eroded the actual purchasing power of low-income households more severely, as they allocate a larger portion of their budgets to essentials like food and energy. On the gender front, while the overall pay gap is slowly closing, structural barriers persist.

The Age of Geo-Economic Fragmentation

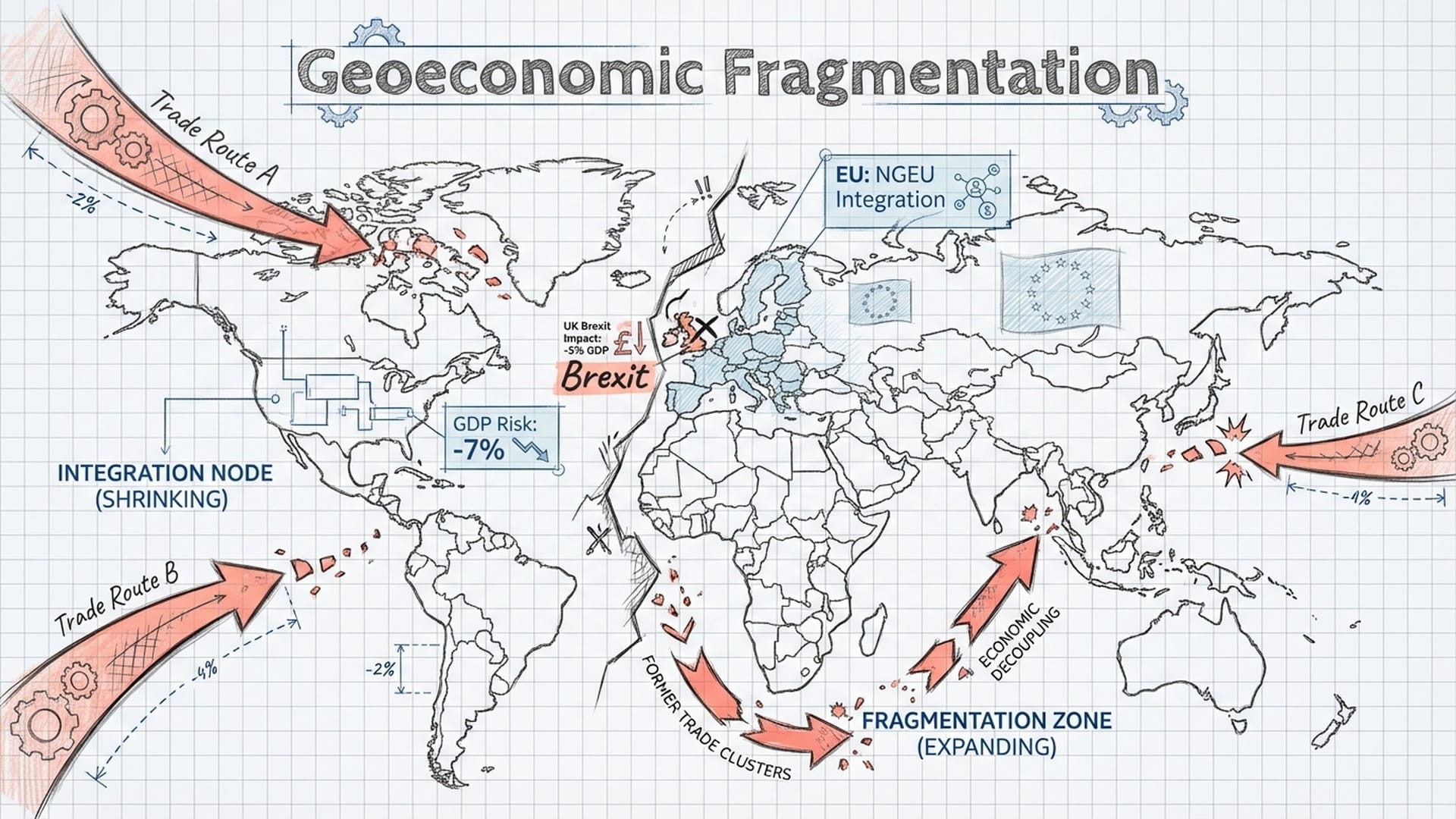

If 2000 to 2015 represented the golden age of globalization, then 2016 to 2025 has been the accelerated era of deglobalization, or geoeconomic fragmentation. This shift has not only reshaped global supply chains but has also become a structural force driving the return of inflation.

Since the 2018 trade wars, the global economic logic has shifted dramatically from pursuing extreme efficiency (e.g., just-in-time practices) to prioritizing security and resilience (e.g., just-in-case strategies). Warnings from the IMF and the Bank for International Settlements are stark: trade fragmentation will significantly reduce global economic output. In the long run, if the world truly splinters into rival trade blocs, global GDP could shrink by as much as 7 percent.

"The shift from prioritizing 'efficiency' to 'security' in global supply chains marks a fundamental reorientation post-2018. While enhancing resilience, this geoeconomic fragmentation undermines the disinflationary forces of open markets and is a key driver of renewed inflationary pressures."

This fragmentation carries clear inflationary effects. Companies, eager to hedge against geopolitical risks, are engaging in near-shoring or friend-shoring. While this boosts supply chain stability, it means abandoning the lowest-cost production locations, pushing up production costs. Research consistently shows that open economies tend to have lower inflation rates, and increasing trade barriers directly undermine this disinflationary force.

Beyond trade barriers, the cross-border movement of labor has also faced severe restrictions. Immigration has historically been a critical driver of U.S. labor growth and a powerful force against wage inflation. However, with tightening immigration policies, this demographic dividend is fading. Estimates suggest restrictive immigration policies could reduce U.S. GDP growth by 0.3 to 0.4 percentage points by 2025. In sectors heavily reliant on immigrant labor, such as construction and hospitality, labor shortages are particularly acute, driving up service sector wages and contributing to stubbornly high core inflation.

What about the future of interest rates? While central banks might cut rates in the short term due to economic slowdowns, there's growing evidence that the long-term natural interest rate, or R-star, might have bottomed out and is now rebounding. The IMF suggests that while aging populations and slowing productivity will continue to exert long-term downward pressure, the normalization of fiscal deficits (driven by defense, green transition investments, and aging-related expenditures) and increased capital expenditure due to deglobalization could offset these forces. This implies we are unlikely to return to the negative or zero-interest-rate world of the 2010s; a higher cost of capital is likely to be a persistent structural feature of the future.

European Experiments: Integration vs. Dissociation

Between 2000 and 2025, Europe conducted two starkly contrasting macroeconomic experiments: the eurozone’s forced deepening of integration through crisis, and the U.K.'s experiment in dissociation through Brexit.

- Eurozone Integration: Jean Monnet's prediction, "Europe will be forged in crises, and will be the sum of the solutions adopted for those crises," has proven true. The 2010-2012 sovereign debt crisis highlighted institutional flaws. However, the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic became a catalyst for integration. The EU launched the 750 billion Euro

NextGenerationEU (NGEU)recovery plan, marking the first time it issued large-scalecommon bonds. This signified a substantial step towards becoming afiscal union, stabilizing market confidence and preventing a second sovereign debt crisis. - Brexit's Economic Impact: In stark contrast, Brexit has imposed a structural, negative shock on the British economy. The U.K.'s Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts a 4 percent reduction in U.K. productivity and a 15 percent drop in export and import intensities compared to remaining in the EU. Real-world data confirms this: the U.K.'s trade recovery post-pandemic has lagged, and business investment remains low. The Centre for European Reform (CER) estimates that by 2024, the U.K.'s GDP was approximately 5 percent lower than it would have been without Brexit, with an investment gap as high as 10 percent. Modest regulatory adjustments offer only marginal recovery.

Can AI Save Us? The Productivity J-Curve

Against this backdrop of shrinking workforces and ballooning debt, technological progress is seen as the last, best hope for sustained economic growth. Since 2023, the explosion of generative artificial intelligence (AI) has dominated global economic discourse. But is this merely the Solow Paradox 2.0?

Nobel laureate Robert Solow famously quipped in 1987, "You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics." This paradox appears to be replaying with AI. Generative AI adoption is incredibly fast, reaching 54.6 percent in the U.S. by August 2025, far outstripping the diffusion speed of personal computers and the internet at similar points. Yet, a macro-level surge in productivity data remains elusive.

Can AI truly deliver a productivity revolution? Erik Brynjolfsson and other scholars offer a powerful explanation with their Productivity J-Curve theory. This theory posits that when general-purpose technologies (GPTs) like AI are first introduced, companies must invest heavily in intangible assets:

- Process redesign

- Employee training

- Developing new business models

These investments do not immediately translate into increased output; they initially consume resources, temporarily lowering measured productivity. It is only when these intangible investments mature into actual productive capabilities that productivity truly takes off.

"The 'Productivity J-Curve' offers a crucial lens through which to view AI's economic impact. We are currently at the bottom of the 'J', where intensive investment in intangible assets precedes the explosive gains in productivity that artificial intelligence promises for the future."

We are currently at the bottom of that J-curve. While macro data may not yet reflect it, micro-level evidence is compelling. PricewaterhouseCoopers data shows that jobs requiring AI skills command a wage premium of up to 56 percent, with their wages growing twice as fast as other jobs—a clear signal that the market is already pricing in AI's productivity potential. Goldman Sachs and McKinsey predict that AI's substantial boost to GDP will become apparent around 2027 and peak in the early 2030s.

AI is expected to contribute 0.2 to 0.3 percentage points to annual productivity growth, potentially raising GDP levels by several percentage points in the long run. While this may not sound significant, through the power of compounding, it becomes a critical force to offset the negative impacts of an aging global population.

The New Economic Reality: 2000-2025 and Beyond

Looking back at the global economic journey from 2000 to 2025, we witness a profound story of old orders crumbling and new ones being painstakingly rebuilt. The key takeaways for this new economic era are:

- End of Macroeconomic Stability: The era of low inflation, low interest rates, and accelerated globalization—the

Great Moderation—is over. The future economy will frequently face supply-side shocks (e.g., climate change, geopolitical tensions, pandemics), significantly increasingmacro volatility. - Age of Fiscal Dominance: Central banks are no longer the sole economic saviors. Against a backdrop of rising populism and strategic competition, fiscal policy will play a greater role, implying that deficits and debt will remain high, and the central tendency of interest rates will move upwards.

- Rebalancing Efficiency and Resilience: The global economy is shifting from an extreme efficiency orientation to one focused on

securityandresilience. While this will sacrifice some growth and potentially push up inflation, it will also enhance economies' ability to withstand extreme shocks. - Race Between Technology and Demographics: As developed economies, and even China, grapple with deep aging,

AI-driven productivity gainsare no longer a luxurious bonus but a necessary condition to maintain existing living standards and social contracts.

The world of 2025 is more fragmented than the world of 2000, yet it is also more acutely aware. The blind faith in market self-regulation has been supplanted by a renewed scrutiny of state capacity, social safety nets, and supply chain security. In this new era of uncertainty, adaptability and resilience will be the keys to survival and prosperity for all economies.

|  |  |