Fixed: How Behavioral Finance Reveals the R-word in Financial Markets

Explore how the financial system is 'fixed' to exploit human behavioral quirks. This deep dive into 'Fixed: Why Personal Finance Is Broken and How to Make It Work for Everyone' uncovers market inefficiencies, the truth about 'dumb money,' and strategies for contrarian investors.

|  |  |

The way many individuals perceive and interact with money, alongside the fundamental beliefs underpinning investment strategies and even the architecture of our financial markets, is, at its core, deeply flawed. This isn't merely an accidental deviation; it's a system that often appears to be deliberately fixed – like a game rigged from inception. For decades, the financial world has largely operated under the Efficient Market Hypothesis, positing that investors are perfectly rational agents who process information seamlessly, make optimal decisions, and that market prices inherently reflect all available wisdom. While a comforting idea of a fair and equitable game, this notion has been systematically dismantled by scholars like John Y. Campbell and Tarun Ramadorai in their seminal work, Fixed: Why Personal Finance Is Broken and How to Make It Work for Everyone. They highlight not just inefficiencies but a financial ecosystem riddled with structural flaws that actively exploit inherent human cognitive biases.

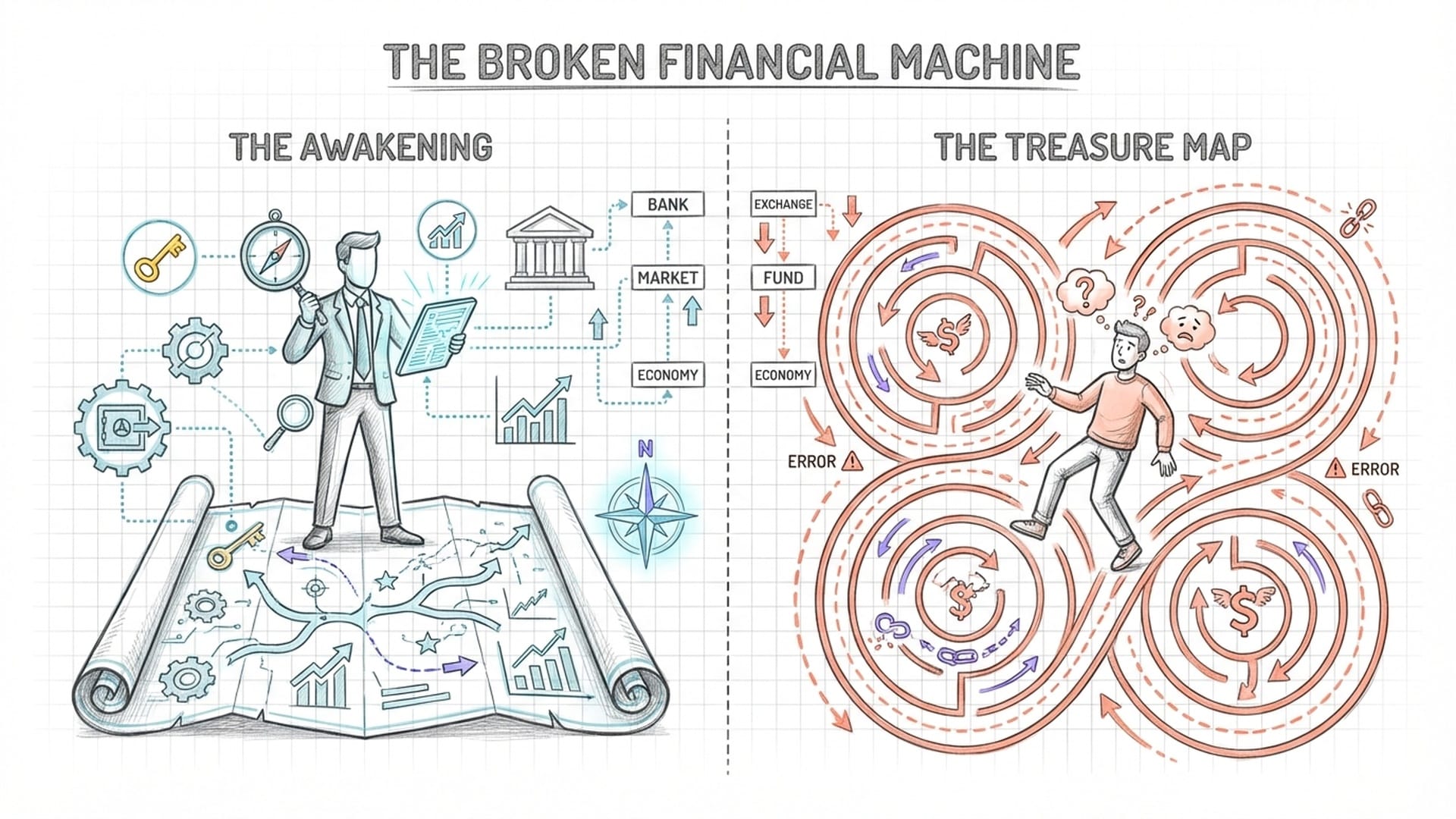

Unmasking the Flaws: A Treasure Map for Contrarians

For the average individual, this revelation serves as a critical wake-up call, underscoring the urgent need for enhanced financial protection. However, for a specific breed of investor – the contrarian who discerningly identifies patterns amidst ostensible chaos – this perspective transcends mere revelation; it offers a profound treasure map. It illuminates the predictable avenues through which wealth is often transferred from the unsuspecting to the astute. By meticulously analyzing how dumb money consistently succumbs to pitfalls – driven by inertia, an insatiable craving for instant gratification, or simply inadequate diversification – the sophisticated investor gains an almost unparalleled advantage. This allows them to anticipate shifts in liquidity, foresee regulatory changes, and precisely time exits from markets fueled by retail exuberance.

This isn't about deciphering complex trading algorithms, which have, ironically, become a commodity themselves. Instead, it delves into something far more fundamental and inherently human: behavioral arbitrage. This is the art of strategically profiting from the predictable, persistent, and structural errors made by ordinary households, and the regulatory responses these errors inevitably provoke.

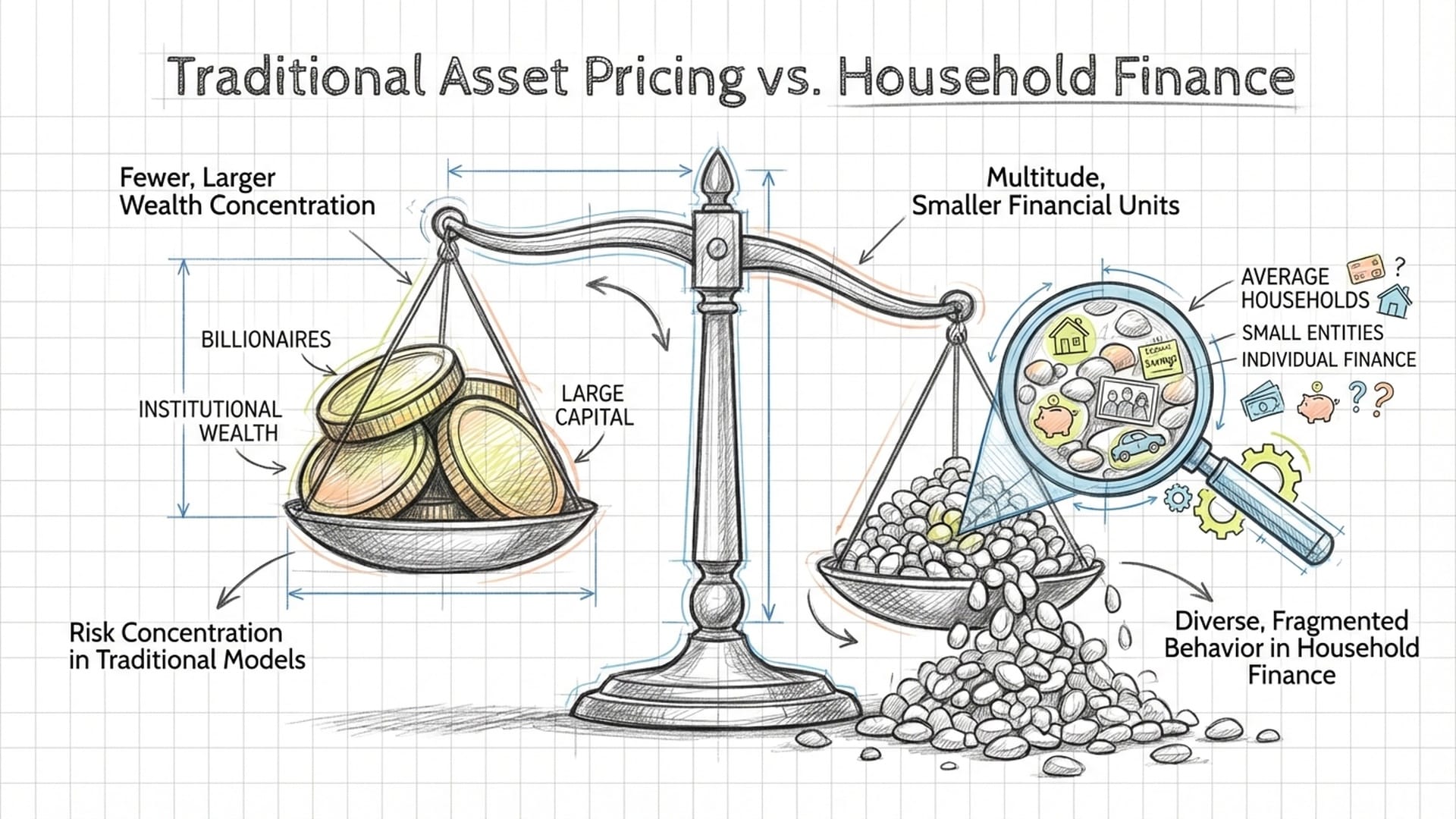

A Paradigm Shift: From Price-Weighted to Equal-Weighted Finance

To truly grasp these dynamics, one must first recognize a seismic shift in how finance is conceptualized. Historically, financial economics was almost exclusively preoccupied with prices. Traditional asset pricing models, for instance, are inherently wealth-weighted. This means they largely focus on the actions of major players – billionaires and institutional investors – whose substantial capital decisions shape market prices. The individual, small-scale investor was largely considered static or noise, their irrational behaviors quickly ironed out by the smart money.

"For generations, financial economics was almost exclusively fixated on prices... The small investor was, in essence, just static, a minor disturbance that the 'smart money' would quickly iron out."

However, Household Finance – a field championed by Campbell – completely inverts this perspective. Rather than scrutinizing the strategies of the wealthy, it meticulously examines the typical household from an equal-weighted view. The focus shifts to understanding the welfare, behaviors, and, crucially, the mistakes of the average person.

What this novel lens reveals is nothing short of breathtaking: the cumulative impact of individual household errors is not mere noise; it constitutes a colossal, enduring inefficiency that profoundly shapes market dynamics. These inefficiencies, contrary to rational expectations, are not dissipating. Why? Because the very industry poised to arbitrage these anomalies often possesses a deep, vested interest in their perpetuation. They aren't in the business of rectifying your mistakes; more often, they are adept at packaging and reselling them.

"The cumulative effect of individual household errors isn't just noise; it’s a colossal, enduring inefficiency that shapes markets. And the kicker? These inefficiencies aren't disappearing."

For the contrarian, this reframes the entire investment landscape. If the market is indeed bifurcated between smart money dictating prices and dumb money providing liquidity – often at the most disadvantageous times – then comprehending the behaviors of dumb money becomes the ultimate key to deciphering the movements of smart money. Campbell and Ramadorai provide a precise, almost scientific classification of these dumb money behaviors, revealing that your "opponents" are not anonymous forces, but rather ordinary individuals falling prey to predictable human instincts.

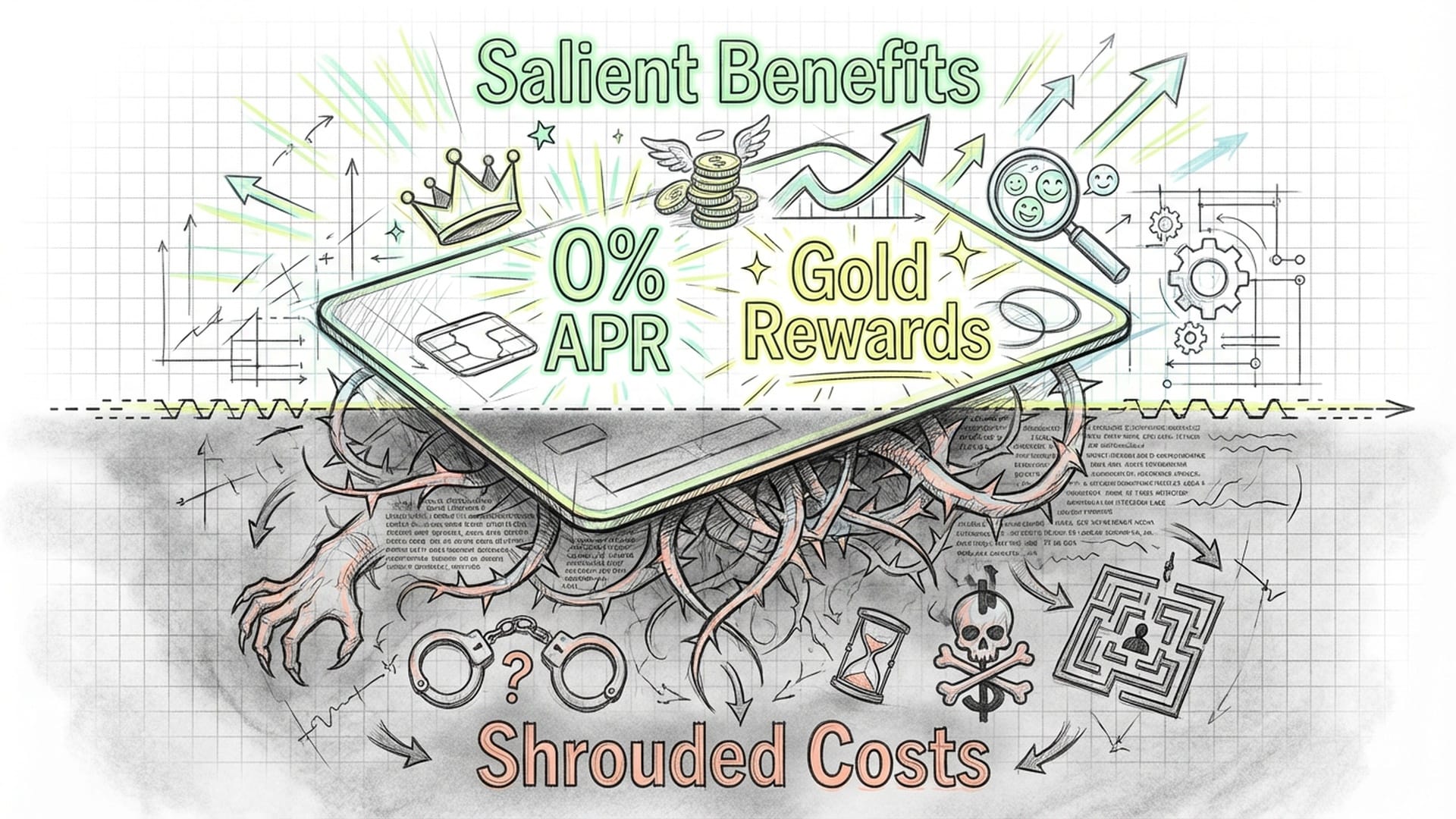

The Toxic Interaction: How Competition Perverts Personal Finance

At the core of Fixed resides the concept of the toxic interaction. This isn't just an evocative phrase; it's a brutal deconstruction of how competition in the personal finance sector operates in a profoundly perverse manner. Instead of fostering lower costs and improved services, it often escalates complexity and deliberately cloaks true costs in a labyrinth of fine print.

Financial institutions entice consumers with alluring salient benefits: think of those ubiquitous zero percent introductory APRs on credit cards, attractive rewards programs, or deceptively low teaser rates on adjustable mortgages. These features are designed to be immediately visible and irresistibly appealing. Yet, these glittering promises are almost invariably tethered to shrouded costs: escalating late fees, exorbitant interest rates after introductory periods, byzantine backend fee structures, or punitive reset terms that can devastate a household budget.

This dynamic engineers a financial alchemy – a cross-subsidization that forms the very lifeblood of the retail financial sector.

- Who benefits?: The

sophisticatedusers, typically the financially literate and affluent. They adroitly cherry-pick benefits without ever triggering the associated costs. They pay credit card balances in full, accrue substantial rewards points, ruthlessly refinance mortgages at opportune moments, and deftly avoid overdrafts and maintenance fees. - Who pays?: The

naiveconsumers, who readily fall into behavioral traps. These individuals are often less affluent, less educated, and already burdened by heavier cognitive loads.

The profound insight for a contrarian investor is that the vast majority of corporate profits in the retail financial sector are not rooted in consumer success but are, in fact, derivatives of consumer failure.

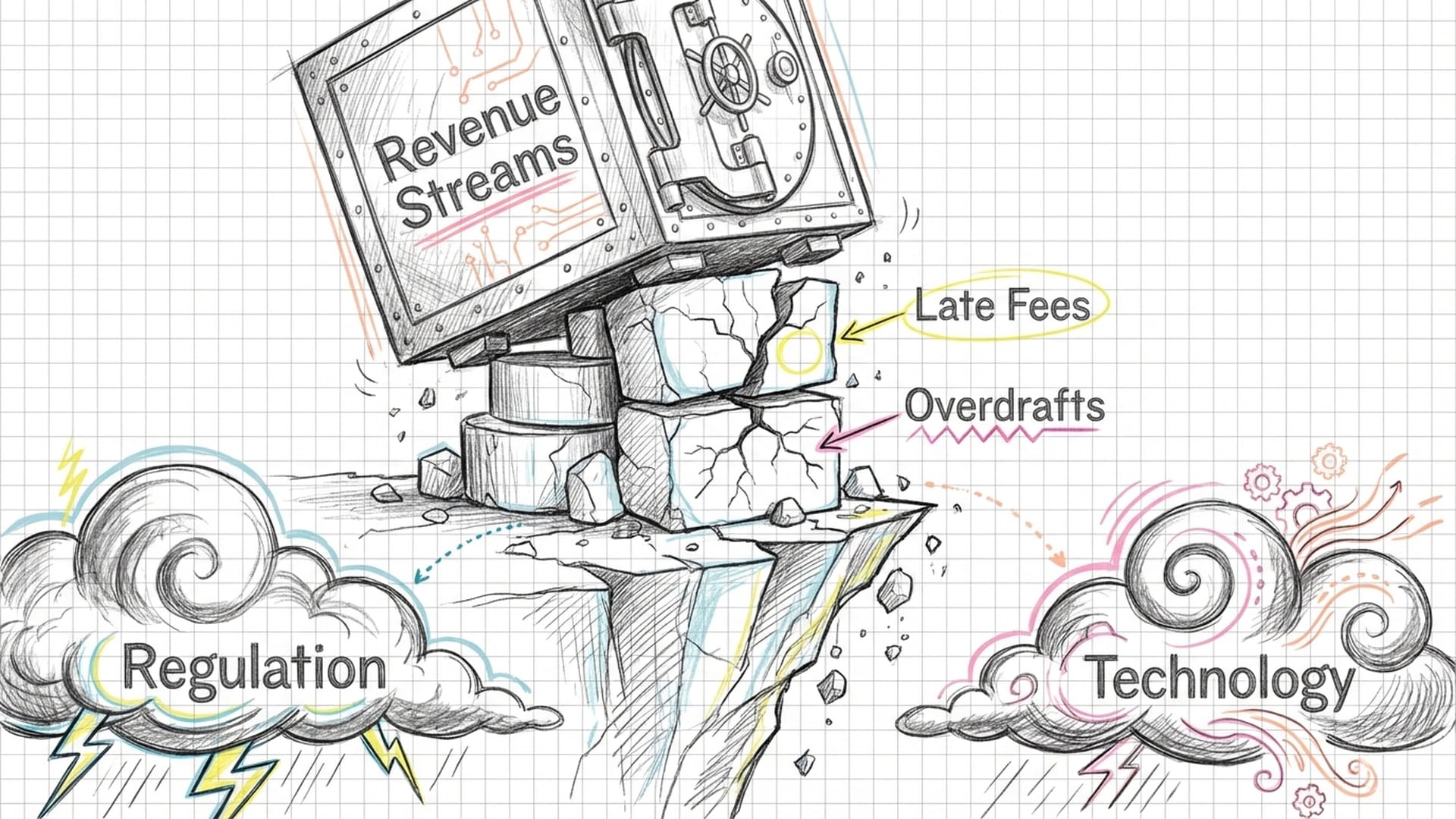

Fragile Foundations: Profit Built on Mistakes

When analyzing the earnings reports of credit card issuers, mortgage servicers, or retail banks, a critical question emerges: How much of this impressive Net Interest Margin or fee income is genuinely built on the back of mistakes? If a significant portion of revenue relies on late fees, overdrafts, or suboptimal refinancing choices, then that revenue stream is not merely unsustainable; it is exquisitely fragile. It teeters precariously, vulnerable to two potent forces:

- Technological Advancement & Financial Education: Imagine a future where technology empowers consumers with automated tools – apps that ensure timely payments, smart budgeting that flags issues proactively. As these solutions become widespread, the pool of

mistake revenueinevitably shrinks. - Regulation: Even more menacing for these institutions is the looming shadow of robust regulation. A true

shove, as Campbell terms it, that simplifies financial products and shields consumers from these predatory traps, would pose an existential threat to these entrenched business models.

The toxic interaction isn't solely a driver of inequality; it is, ironically, the primary engine of profit for many established financial institutions. Understanding this engine is paramount to assessing the long-term durability of these profits.

The Roots of Inefficiency: Human Biases and Market Distortions

To adeptly exploit these market inefficiencies, one must first comprehend their origins. This isn't some vague economic concept; it's the precise, measurable outcome of human psychology clashing with intricate financial mathematics. Campbell and Ramadorai have meticulously categorized these deviations from rational behavior, illustrating them not as random anomalies but as systematic, predictable biases that redirect massive capital flows and distort asset prices.

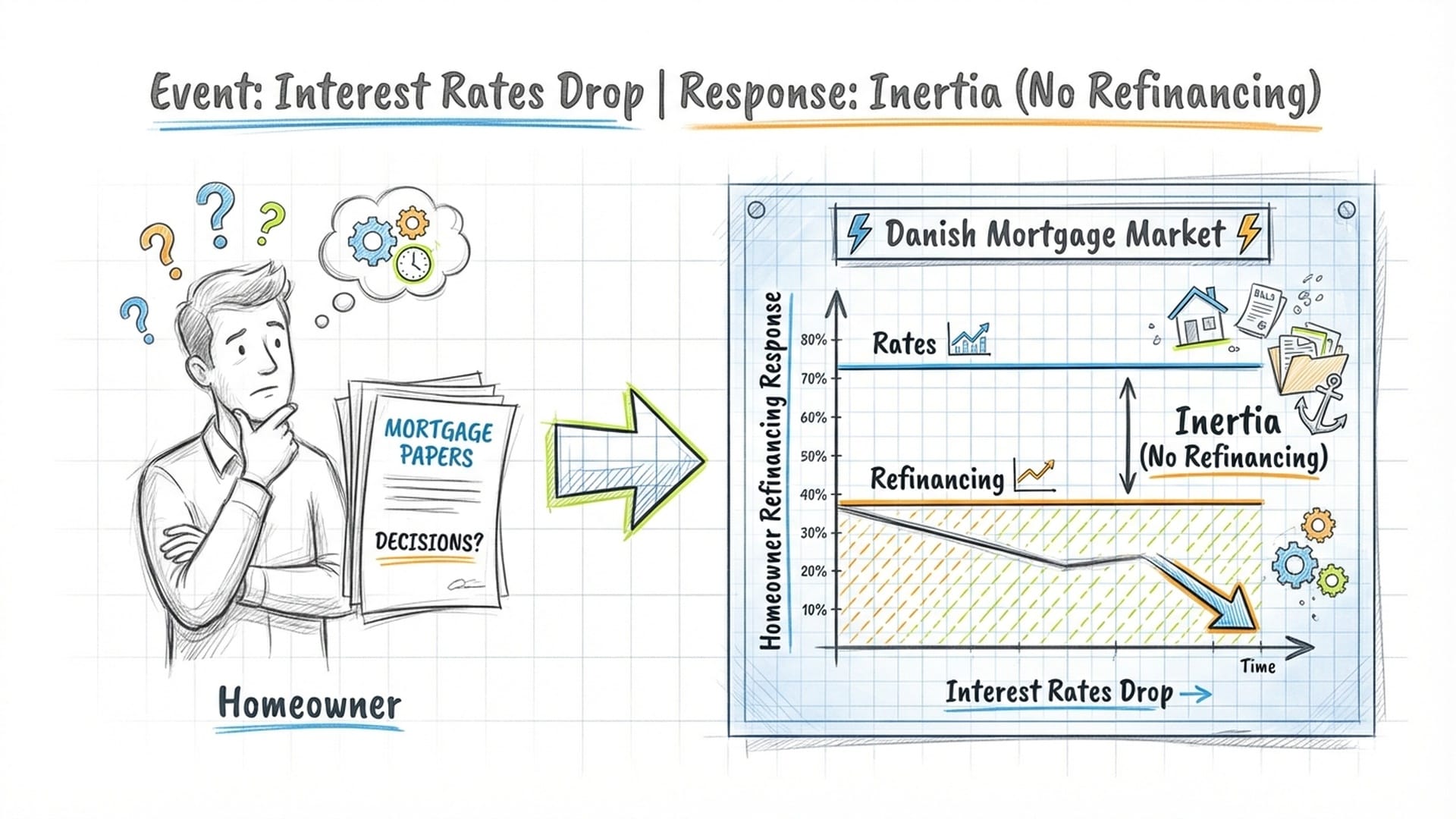

1. Inertia: The Power of Doing Nothing

Perhaps the most insidious force in household finance is not greed or fear, but simply inertia. People inherently favor the status quo. Households exhibit a profound status quo bias due to perceived or actual fixed costs associated with altering their financial arrangements. These costs can be:

- Physical: The sheer drudgery of paperwork or visiting a branch.

- Cognitive: The mental exertion required to comprehend dense fine print or compare complex financial products.

- Psychological: The nagging anxiety of making an incorrect decision.

This leads to inattention, where optimizing actions are simply delayed or entirely ignored.

Consider the vivid example of the Danish mortgage market. Campbell's research consistently demonstrates that a staggering percentage of households neglect to refinance their mortgages, even when interest rates plummet, forfeiting thousands of dollars. This isn't due to a lack of options but a profound lack of attention.

"The contrarian insight here is golden: for MBS trading, the 'prepayment risk' is often wildly overstated by those rational models. The 'inattention gap' provides a critical buffer for holders of high-coupon MBS..."

The market impact of this behavior creates sticky liabilities. In the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) market, purely rational prepayment models are often confounded. The inattention gap dampens the expected wave of refinancing, sometimes for years, providing a crucial buffer for holders of high-coupon MBS. Conversely, companies that profit from breakage – unredeemed gift cards, unused subscriptions, dormant low-yield deposits – trade at a premium precisely because of customer inertia. The astute investor identifies firms where customer inertia is a dominant asset and avoids those whose profitability hinges on constant customer activity.

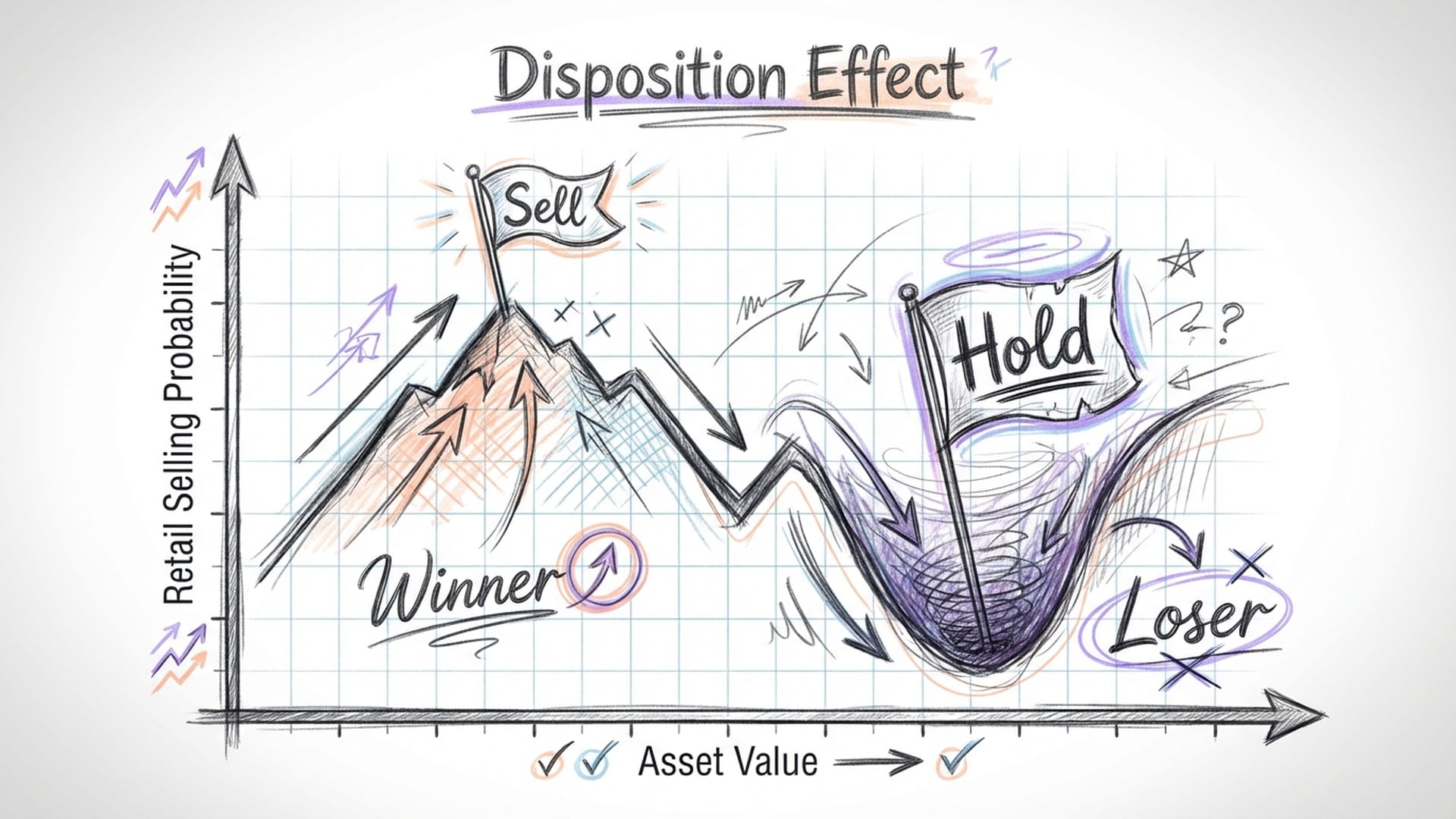

2. The Disposition Effect: Selling Winners, Holding Losers

The disposition effect, a cornerstone of Kahneman and Tversky's Prospect Theory, vividly illustrates another human bias. Investors possess an almost irresistible urge to sell assets that have appreciated in value – to lock in a win and validate their ego. Concurrently, they desperately cling to assets that have incurred losses, because realizing a loss is profoundly psychologically painful (loss aversion indicates the pain of a loss is roughly twice as intense as the pleasure of an equivalent gain).

The market consequences are clear: this behavior generates artificial headwinds for winning stocks and an artificial floor for losing stocks.

- When a stock rises, retail investors often sell to

bank the profit, increasing supply and capping the price below its true fundamental value. - When a stock declines, retail investors stubbornly

clutch it tightly, artificially restricting supply and delaying the inevitable discovery of its lower, true value.

For the contrarian, this is a clear validation of momentum strategies. By acquiring winners that retail investors prematurely abandon and divesting losers that they desperately cling to, sophisticated investors effectively supply liquidity to dumb money at a premium. The disposition effect thereby elongates market trends, enabling them to persist far longer than they would in a truly efficient market.

3. Present Bias and Hyperbolic Discounting: The Perils of Instant Gratification

The Beta-Delta model of present bias elegantly explains a persistent puzzle for traditional economists: why do households borrow at exorbitant credit card rates while simultaneously maintaining perfectly liquid assets in low-yield savings accounts? Standard economics struggles with this, but behavioral economics provides the answer: immediate gratification profoundly outweighs the exponential cost of future repayment. Humans dramatically and discontinuously value the now far more than the later.

"Rational models assume borrowing is for clever 'consumption smoothing' over a lifetime. Behavioral models understand it's often just a sheer lack of impulse control."

This fuels the perpetual consumer credit cycle. Retail consumption is often supercharged by an irrational assessment of future repayment capacity, with consumers essentially renting their current lifestyle at usurious rates, deluding themselves into believing future discipline will materialize.

A contrarian insight emerges here: when aggregate consumer credit balances visibly decouple from wage growth, it often signals that present bias has reached a breaking point. This is a crucial leading indicator for potential credit quality deterioration. An investor looking to short the consumer discretionary sector would meticulously monitor for the moment when the cost of servicing this present bias debt overwhelms consumers' capacity to simply borrow more.

The Dumb Money Signal: Retail Inflows as a Contra-Indicator

Perhaps the most direct signal for the investor lies in the concrete concept of dumb money flows. Extensive research by Campbell, Frazzini, and Lamont incontrovertibly demonstrates that retail mutual fund inflows are a robust, almost infallible contra-indicator. The mechanism is simple: retail investors are fixated on chasing past performance, pouring money into funds after they've had spectacular runs (buying high) and withdrawing money after agonizing underperformance (selling low). This is the quintessential buy high, sell low strategy.

- Market Impact: Sky-high retail sentiment inflates asset prices beyond their fundamental value, reliably predicting abysmal future returns. Similarly, periods of massive corporate equity issuance often align with this frothy retail sentiment, as corporations (the

smart money) capitalize by expanding supply precisely whendumb moneyis ravenously demanding it. - Contrarian Insight: Tracking fund flow data is not optional; it is essential. A sudden, dramatic surge in retail inflows into a specific sector or asset class (e.g., "Tech Funds," "Crypto ETFs," or "ARK-style funds") is almost always a reliable sell signal. Conversely, massive, panicked outflows often signify a capitulation bottom, offering an ideal entry point for sophisticated liquidity providers. When flows diverge sharply from fundamentals,

smart moneysteps in.

Deconstructing Fixed: Products and Mechanisms Engineered for Exploitation

Campbell and Ramadorai argue that the financial system isn't accidentally flawed; it's fixed because it has been intricately designed to harvest these behavioral mistakes. This is not a random byproduct of capitalism but the highly optimized outcome of financial firms relentlessly pursuing shareholder value within a regulatory environment that has, for too long, permitted this complexity to flourish.

Let's dissect some products and mechanisms, viewing them not just as consumer traps, but as ruthlessly efficient business models:

1. The Mortgage Market: A Labyrinth of Inattention and Complexity

The mortgage market, representing the largest financial transaction for most individuals, is paradoxically rife with suboptimal decision-making. The authors adeptly demonstrate how its architecture exploits inattention and difficulty with complexity.

- The Adjustable Rate Mortgage (ARM) Trap: ARMs are consistently marketed with seductive

teaser rates. While theoretically justifiable for niche borrowers, they are often sold to individuals who profoundly misunderstand the inherent interest rate risk. Theteaserrate cleverly exploits present bias, leading borrowers to fixate on low initial payments while discounting future reset risks. - Systemic Failure to Refinance: The widespread failure of homeowners to refinance fixed-rate mortgages when interest rates drop constitutes a colossal transfer of wealth from ordinary households to bondholders. This isn't accidental; the refinancing process itself is often deliberately laden with friction – extensive paperwork, costly appraisals, mandatory title insurance. Why? To discourage

efficientbehavior. If refinancing were frictionless, MBS values would plummet as theiroption costwould be instantly realized. This manufactured friction directly safeguards investor yield.

Campbell's radical proposal, the Ratchet Mortgage, would automatically adjust rates downward when market rates fall but never upward, eliminating friction-laden refinancing. The fact that this elegant, pro-consumer product is not widely adopted is telling – it suggests the industry prefers the friction, which generates lucrative fees. The persistent absence of the Ratchet Mortgage is damning evidence that the system is, indeed, Fixed, prioritizing fee generation over consumer welfare.

2. Credit Cards: The Toxic Interaction at its Apex

Credit cards represent arguably the clearest and most brutal manifestation of the toxic interaction. Their model is ingenious, if sinister: high rewards (points, cash back, lounge access) are aggressively marketed to attract sophisticated users. These lavish rewards are funded from two primary sources:

- Interchange fees: Charged to every merchant.

- Crushing interest and late fees: Paid by

revolvers(those who carry balances) andforgetfulindividuals (those who miss payments).

This structure creates a reverse Robin Hood effect, systematically transferring wealth from less educated or poorer segments (who bear the fees and exorbitant interest) to the wealthier segments (who effortlessly accrue rewards). The 2% cash back received by a prime borrower is effectively subsidized by the 25% APR paid by a subprime borrower.

The investment implication is stark: credit card issuers face a binary risk. While current high profitability may persist indefinitely under unregulated toxic interaction, any serious regulatory scrutiny on junk fees or interest rate caps (a shove) would decimate their economics. If the subsidy from the poor is severed, rewards for the rich must diminish. A contrarian identifies high-margin credit card issuers as uniquely vulnerable to populist regulatory action demanding simplification.

3. Insurance and Annuities: The Annuity Puzzle

In insurance and annuities, households consistently over-insure trivial risks (e.g., overpriced extended warranties) while catastrophically under-insuring truly massive risks, particularly longevity risk through annuities. This is known as the annuity puzzle. Standard economic theory dictates that as people age, facing the risk of outliving savings, they should demand annuities – the only financial product guaranteeing a lifelong income stream. Yet, annuities remain woefully unpopular.

Campbell attributes this to framing. Consumers perceive annuities merely as investments with low returns and a loss of control, rather than as insurance against poverty in old age. They focus on the perceived loss of their lump sum instead of the undeniable gain of lifelong security.

Here lies a contrarian opportunity: if Campbell's proposed starter kit – standard financial products – gains traction, it would likely include default enrollment in sensible longevity products. This would create a massive, secular tailwind for insurers specializing in simple, low-cost annuities, while posing an existential threat to brokers selling complex, high-commission variable annuities that thrive on consumer confusion. The true alpha lies not in exotic products, but in identifying transparent, low-cost providers poised for a market where annuities are intrinsically bought, not laboriously sold.

The Prescription: A Shove, Not Just a Nudge

Campbell and Ramadorai move beyond diagnosis to prescribe a detailed remedy. They categorically reject the nudge philosophy, deeming these gentle behavioral prompts insufficient. Instead, they advocate a shove – a far more robust, even mandatory, regulatory architecture.

Their core proposal is the Financial Starter Kit: a set of safe, meticulously regulated default products available to every citizen – essentially a public option for finance. The fundamental principle is that the default financial choice should always be the safest and most beneficial. This protected ecosystem would comprise three standardized pillars:

- Universal, Portable Retirement Account: A Roth structure with automatic enrollment into low-cost index funds, following individuals job-to-job, eliminating 401(k)

leakage. - Standard

Plain VanillaMortgage (orRatchet Mortgage): Protecting borrowers from rate spikes while allowing them to benefit from rate drops, thus removing the need for complex refinancing decisions. - Perfectly Structured Emergency Savings Account: Separate from checking, paying market interest rates, and devoid of

gotchafees.

This ecosystem approach directly challenges the fragmented, opaque strategies of current banks, which deliberately silo checking, savings, and investments to maximize fee extraction.

"A 'shove' regime would fundamentally commoditize consumer finance. Margins would collapse as hidden fees are outlawed and complexity is ruthlessly stripped away."

A shove regime would fundamentally commoditize consumer finance. Margins would collapse as hidden fees are outlawed and complexity is eliminated. The alpha for financial firms would pivot from exploiting mistakes to achieving unparalleled operational efficiency. Firms operating at the lowest cost, fueled by sheer scale, would prevail, while those relying on Confusopoly (profiting from deliberate confusion) would be obliterated.

The Contrarian's Playbook: Short Confusion, Long Simplicity

The critical question for the contrarian is the likelihood of these radical proposals materializing. Endorsed by financial luminaries (Bernanke, Gopinath, Rajan), these ideas are rapidly entering the central banking consensus. While legislative gridlock may delay direct adoption, powerful regulatory bodies like the CFPB and SEC possess immense authority to implement shoves via rulemaking. The ongoing trend toward eliminating junk fees perfectly aligns with the book's philosophy.

For the investor who truly comprehends Fixed, value lies not just in diagnosing ailments but in exploiting inevitable market corrections and persistent inefficiencies. This understanding translates directly into a concrete investment playbook: if systemic household errors are predictable, we can consistently trade against them. Dumb money isn't random; it's startlingly predictable.

Investment Strategies:

- Short

Dumb MoneyMomentum:- Signal: Retail inflows into specific thematic ETFs (AI, Cannabis, Crypto, ARK-style funds) reach two standard deviations above their mean.

- Trade: High-probability short.

Dumb moneyis effectively signaling a market top. Wait for sustained inflows even as price action stalls – a classic divergence.

- Liquidity Provisioning /

Buying Fear:- Signal: During market panics, households, driven by

loss aversion, sell indiscriminately in aflightresponse. - Trade: The contrarian acts as a liquidity provider, buying during these

fire sales.Dumb moneydesperately demands liquidity at any cost;smart moneysells it to them at a premium, buying cheap.

- Signal: During market panics, households, driven by

- Arbitrage the Disposition Effect:

- Signal: Identify stocks with high retail ownership that have recently broken out to new highs.

- Trade: Go long. Retail investors, eager to

lock insmall gains, sell into this strength, creating an artificial drag on the price. This suggests the stock is undervalued relative to its nascent momentum, and the trend will persist longer than retail investors’ patience.

Sectoral Vulnerability: The Short and Long Lists

Fixed functions as a manifesto for future regulation. If its worldview takes hold, certain business models become toxic assets. Sectoral analysis reveals a stark dichotomy:

The Short List (Vulnerable to a Regulatory Shove):

- High-fee Active Asset Managers: Charging 1%+ annually, often underperforming index funds. The

Starter Kitpromotes low-cost indexing; shifting default options will erode their distribution. - Subprime Auto and Payday Lenders: Their entire business model rests on present bias and an inability to calculate true APR. National rate caps or

ability-to-repaystrictures would obliterate them. - Variable Annuity Brokers: Their high backend loads and opacity make them prime targets for a

shovetowards simplicity. - Title Insurance Companies and Legacy Mortgage Servicers: If the

Ratchet Mortgageor automated refinancing gains traction, the friction-based fees they rely on will vanish.

The Long List (Aligned with the Fixed Philosophy):

- Fintech and Robo-Advisors: These platforms automate the

shovevia auto-rebalancing, tax-loss harvesting, and auto-saving, perfectly aligning with the book’s vision by shattering inertia. - Low-Cost Index Providers: Poised for massive gains as investment management commoditizes, favoring scale players over boutique active managers.

- Innovative Lenders: Banks that bravely adopt the

Ratchet Mortgageor truly transparent lending practices will capture immense market share from incumbents burdened by legacygotchaproducts.

In the long run, if the system is truly fixed, capital will inevitably gravitate towards efficiency. The ultimate contrarian bet is to invest in the very infrastructure of simplicity. As Campbell and Ramadorai eloquently argue, the sheer complexity of our current financial system imposes a massive tax on the entire economy. Companies that successfully remove this tax – by offering genuinely one-click financial health – will ultimately accrue the enormous value that currently flows into perpetuating inefficiency.

Fixed is more than a critique; it's a meticulously detailed blueprint of the inherent flaws within the modern financial machine. For the general public, it's a potent call for greater protection. But for the contrarian investor, it is, quite literally, a treasure map, pinpointing precisely where systematic inefficiencies are buried. The toxic interaction creates a persistent, structural distortion in asset prices. For decades, dumb money has unwittingly subsidized smart money through punitive late fees, suboptimal refinancing, and self-destructive buy-high-sell-low behavior.

As information asymmetry decreases and regulatory pressure mounts, the era of easy, unearned value extraction from consumer mistakes is rapidly concluding. The next generation of alpha will not arise from cleverly exploiting confusing products, but from strategically betting on the inevitable, wholesale simplification of the system itself. Until that monumental simplification arrives, the market remains a brutal battleground – a stark contest between inherent human cognitive fragility and the ruthless efficiency of financial institutions. Understanding the precise mechanisms of this battle – inertia, framing, and flow – is the decisive edge that distinguishes the perennial victim from the ultimate victor. The contrarian investor, armed with the profound insights of Household Finance, can calmly observe dumb money chasing its own tail, patiently waiting, with unwavering conviction, to take the other side of the trade.

|  |  |