Commercial Real Estate: The Looming Crisis and Its Impact on Regional Banks

Explore the impending commercial real estate crisis driven by interest rate hikes and hybrid work, threatening regional banks and urban economies. Uncover the 'maturity wall' and 'extend and pretend' strategies shaping the financial landscape from 2024-2026.

|  |  |

The Looming Commercial Real Estate Crisis: A Slow-Motion Repricing with Seismic Impact

The financial world is abuzz with whispers of a looming crisis, not in the frenetic stock markets, but within the seemingly стаid realm of Commercial Real Estate (CRE). This isn't just dry financial jargon; it's a structural shift poised to redefine our cities and banking landscape between 2024 and 2026. The confluence of dramatically altered monetary policy and fundamental changes in how we work has created a potent cocktail threatening the stability of regional banks and the fiscal health of American metropolises.

From Golden Age to Double Shock: The Unraveling Consensus

For years following the 2008 global financial crisis, the economy basked in an era of near-zero interest rates. This period proved to be a golden age for commercial properties, with cheap money fueling robust investment and perpetual growth assumptions. Our financial models and investment strategies were largely built upon this foundation of ever-increasing property values.

However, this consensus has dramatically unraveled. We are now confronting a "double shock" that has fundamentally altered the landscape:

- Rate Shock: The Federal Reserve, battling inflation, implemented aggressive interest rate hikes. This instantly rewrote the economics of real estate valuation.

- Usage Shock: The enduring legacy of the pandemic, the permanent shift to hybrid work, has left office buildings significantly underutilized. Even four years on, many offices operate at a mere 50-60% occupancy. This isn't a temporary dip; it's a lasting behavioral and operational change.

These two forces are not merely co-existing; they are colliding to create a storm that disproportionately impacts regional banks.

"This isn't like 2008, where the pain was spread across millions of homeowners and global financial institutions. No, this crisis is hyper-focused. It's concentrated in the portfolios of your local, regional banks—the very institutions that lend to your small businesses, your communities."

Regional Banks: At the Epicenter of Vulnerability

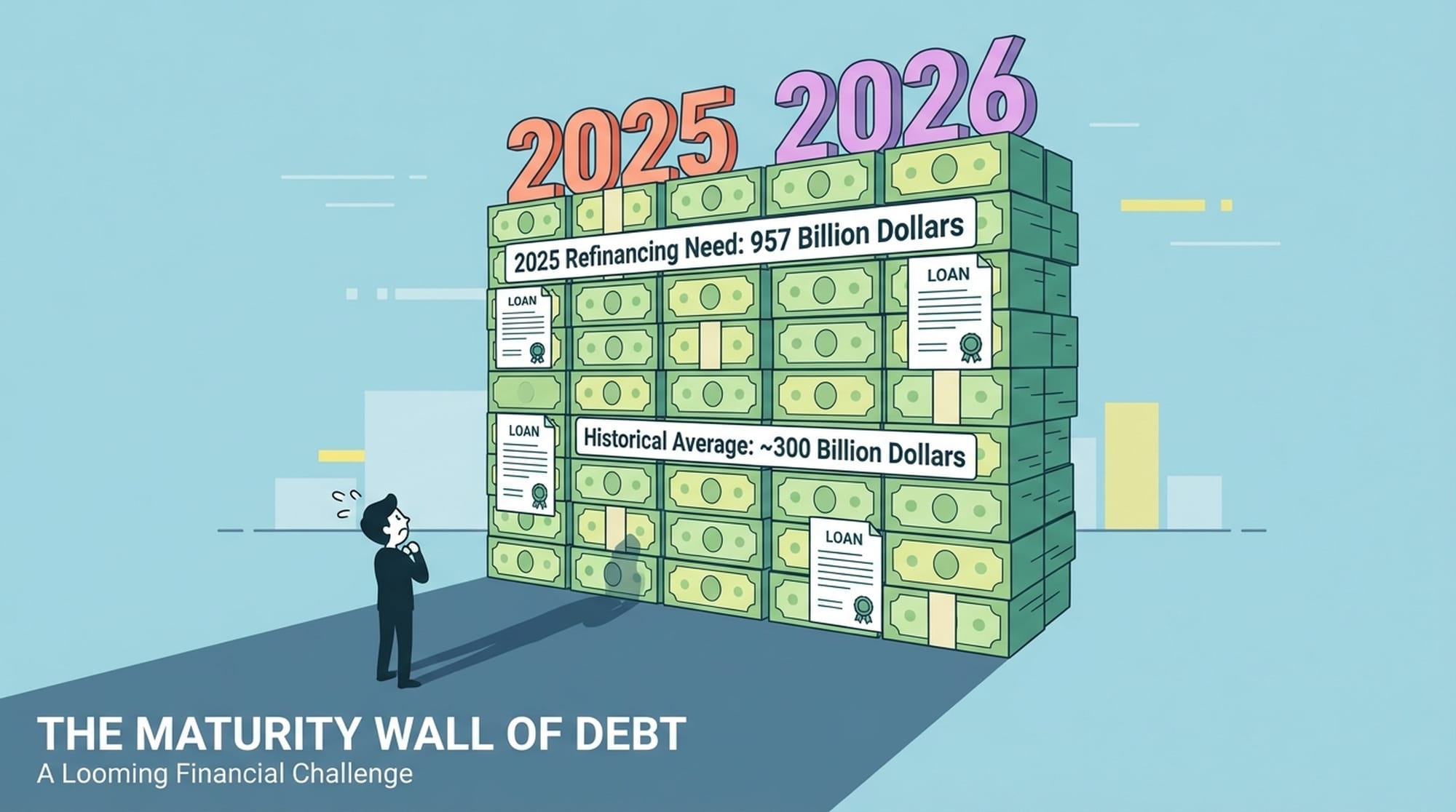

Unlike the diversified exposure of larger financial institutions, regional banks hold a particularly concentrated and vulnerable position. While they account for roughly one-third of all commercial real estate debt, they bear a staggering 70% of the debt slated to mature through 2025. This critical asymmetry highlights their heightened sensitivity to the impending market recalibration.

These banks are now facing a daunting "maturity wall" – an unprecedented volume of debt requiring refinancing in a significantly less favorable environment. In 2025 alone, an estimated $957 billion in commercial mortgages will come due, nearly triple the historical average. The critical question becomes: can borrowers refinance these loans when interest rates are high and their properties have depreciated? The answer will undeniably shape the economic narrative for the remainder of the decade.

The Mechanics of Value Destruction and the Refinancing Gap

Let's dissect how the "double shock" translates into tangible losses. Consider a commercial property generating $1 million in annual income.

- Low-Rate Environment (4% Cap Rate): This building would be valued at $25 million.

- High-Rate Environment (6% Cap Rate): The same income now justifies a value of only $16.6 million – a significant 33% decline.

Given that most commercial real estate is leveraged at 60% to 75%, a 33% drop in property value can entirely wipe out equity. If a $16 million loan was secured against that $25 million property, the owner is now effectively underwater.

Compounding this, borrowers face a brutal reality at refinancing. A loan taken out years ago at 3.5% interest might now require refinancing at 7% or higher. This doubles interest payments, making it almost impossible for property income to cover mortgage obligations. This creates a massive "refinancing gap," demanding fresh capital that many owners lack or are unwilling to inject into a depreciating asset. The inevitable outcome for many? They walk away, handing the keys back to the bank.

"Their interest payments could double, making it impossible for the property's income to cover the mortgage. This creates a massive 'refinancing gap,' demanding a fresh injection of cash that many owners simply don't have or are unwilling to commit to a depreciating asset. So, they walk away, handing the keys back to the bank."

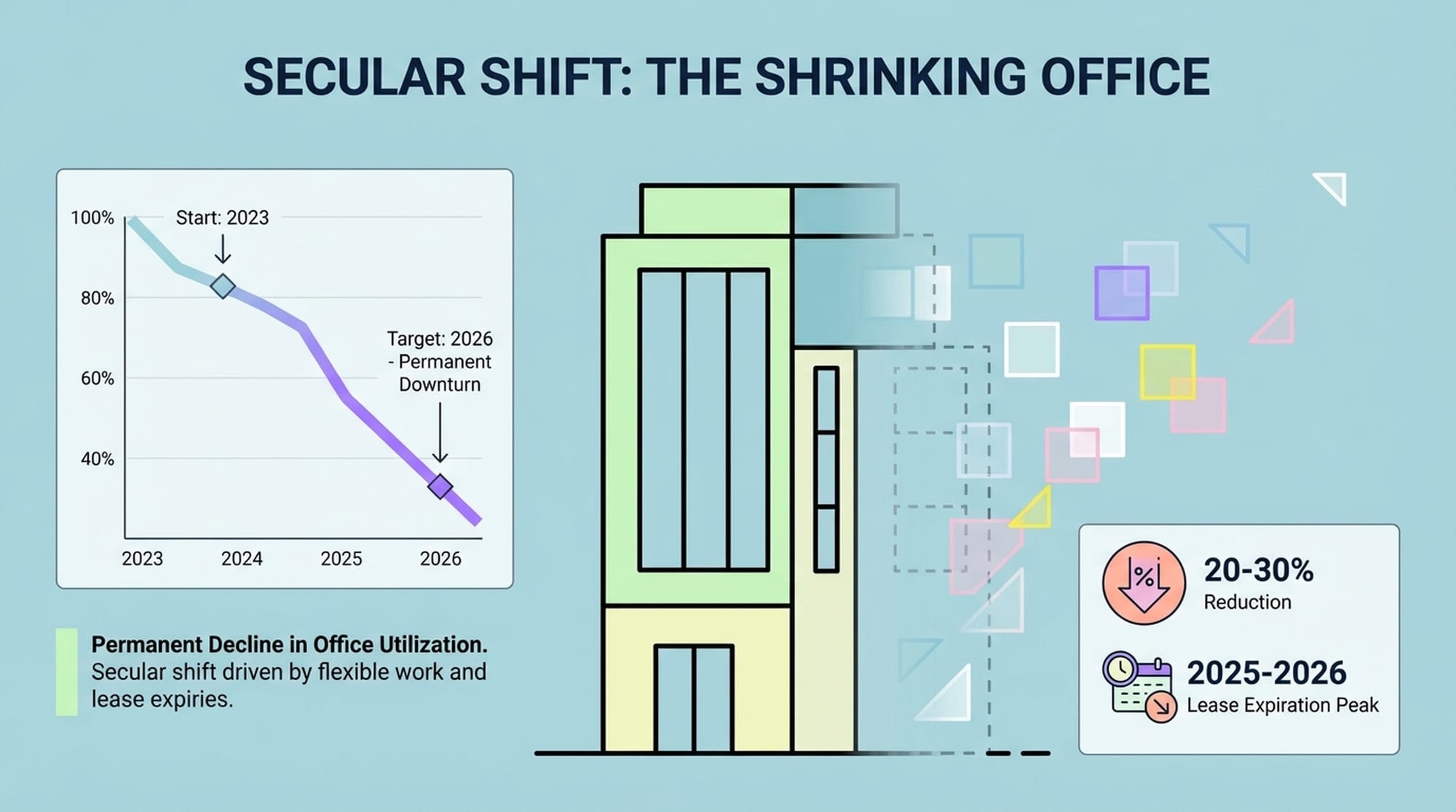

The Secular Shift in Office Space: A Shrinking Footprint

Past real estate downturns were largely cyclical, with demand rebounding post-economic recovery. This time, it's secular. Hybrid work models are here to stay, inherently reducing the demand for office space. Companies can often reduce their physical footprint by 20-30% with a two- or three-day in-office schedule.

The full impact of this reduction has yet to materialize due to the long-term nature of commercial leases (typically 7-10 years). Many leases signed before 2020 are still active, masking the true vacancy rates. The real pain will intensify as these legacy leases expire in 2025 and 2026, coinciding precisely with the maturity wall.

A K-Shaped Recovery: Trophy vs. Obsolete

The decline in CRE is not uniform; it's a K-shaped recovery.

- "Trophy" assets – new, amenity-rich buildings in prime locations – continue to attract demand and maintain value.

- The distress is overwhelmingly concentrated in Class B and C assets: older, less desirable buildings that have become functionally obsolete.

In many submarkets, vacancy rates in these older buildings are catastrophically high. San Francisco serves as a stark warning, with office vacancy rates soaring from under 6% in 2019 to nearly 37% today. Valuations have plummeted by as much as 70%, with buildings that fetched $141 million in 2016 now selling for just $44 million.

The "Extend and Pretend" Strategy: Kicking the Can Down the Road

Given the dire situation, one might wonder why a wave of bank failures hasn't already occurred. The answer lies in the strategy of "extend and pretend." Regulatory frameworks are currently enabling banks to defer immediate losses. A crucial change in 2023 eliminated Troubled Debt Restructuring (TDR) rules, which previously forced banks to declare distress when modifying loans for struggling borrowers. Now, modifications can be made under more lenient criteria, allowing these revised loans to appear as "new" without the stigma of distress.

This means banks are granting short-term extensions (one or two years) rather than foreclosing on properties worth less than the loan amount. This avoids booking immediate losses and explains why the volume of maturing debt in 2025 and 2026 has swelled; it includes loans that should have defaulted earlier but were simply rolled forward.

"Academic research suggests that the reported delinquency rates, which look quite low, are a mirage. 'Latent distress'—loans where the property value is below the loan balance but payments are still being made—might be four times higher than reported delinquencies."

These are "zombie loans," kept alive by the hope that interest rates will magically recede before the extended deadline. The FDIC, while currently solvent, is designed for individual bank failures, not a systemic collapse. Its strategy, by necessity, aligns with "extend and pretend," managing the crisis over time to prevent a cascading effect.

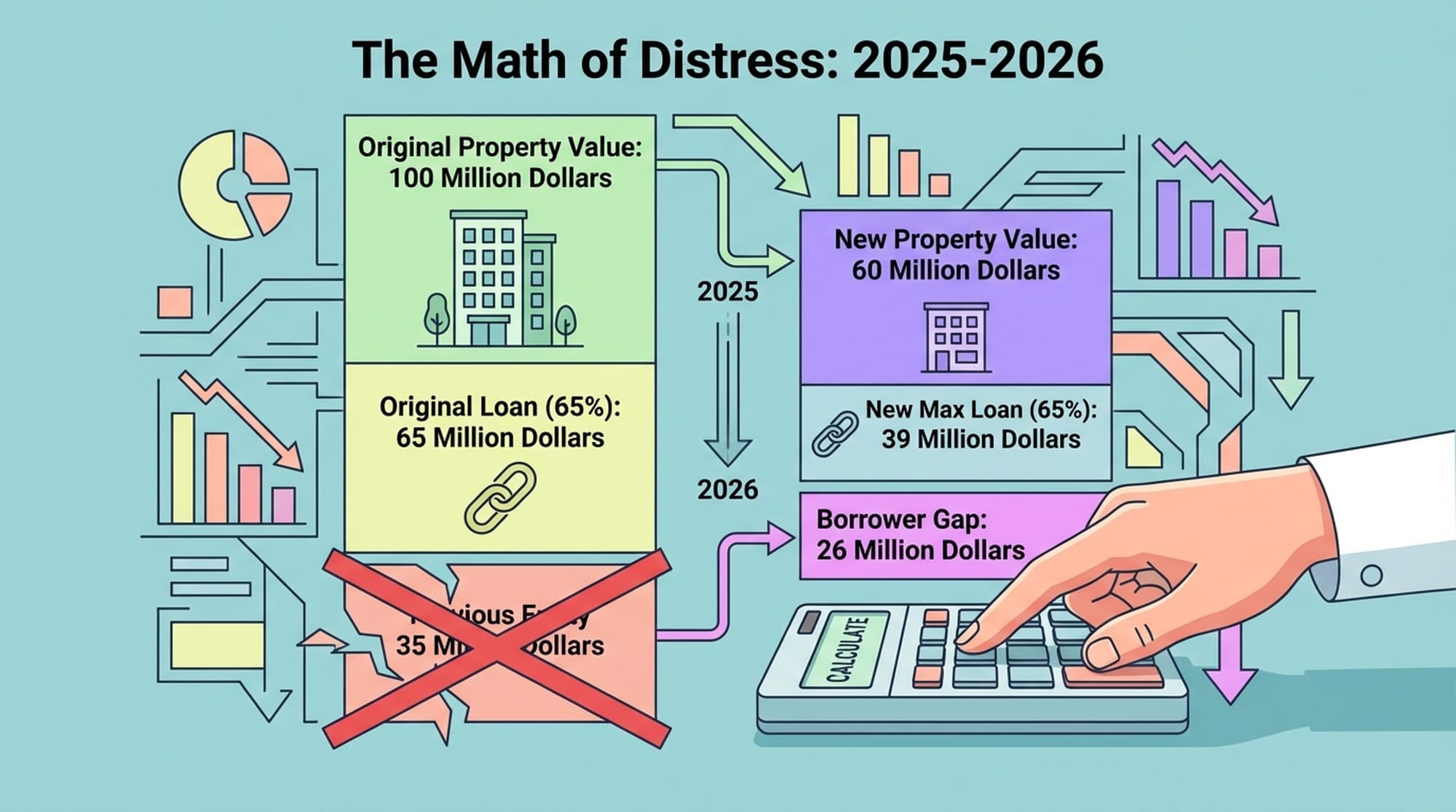

The Math of Distress and the Urban Doom Loop

The period of 2025-2026 represents the moment of truth. Consider a $65 million loan on a $100 million property. If that property is now worth only $60 million, a bank can only lend 65% of the new value – $39 million. The borrower would need to inject a startling $26 million to bridge the gap. When original equity is wiped out, rational owners will walk away, pushing thousands of assets back to banks.

Beyond finance, this crisis is bleeding into the fiscal health of American cities, creating an "Urban Doom Loop." Cities rely heavily on property taxes from commercial buildings. When values collapse, so does the tax base, creating massive revenue holes. San Francisco, for instance, faces a budget deficit exceeding $1.4 billion by 2027, largely due to plummeting office values and reduced transfer taxes from property sales. This forces service cuts, which further drives away residents and businesses, exacerbating the problem. Chicago and Los Angeles face similar challenges.

Mitigating Factors: Not a 2008-Style Abyss

Despite the grim outlook, a catastrophic 2008-style collapse is not inevitable. Several mitigating factors are at play:

- Office-to-Residential Conversions: While gaining traction (70,000 units expected from conversions in 2025), this is a niche solution, not a panacea for the billions of square feet of obsolete office space. Physical realities and high costs limit its widespread applicability.

- U.S. Economic Resilience: The broader U.S. economy's "soft landing" is a crucial buffer. Low unemployment means that multifamily, retail, and industrial sectors remain relatively strong. This diversification helps shield banks from a total portfolio collapse. Furthermore, the Federal Reserve has signaled the end of its tightening cycle, offering the prospect of future interest rate reductions that could relieve pressure on borrowers.

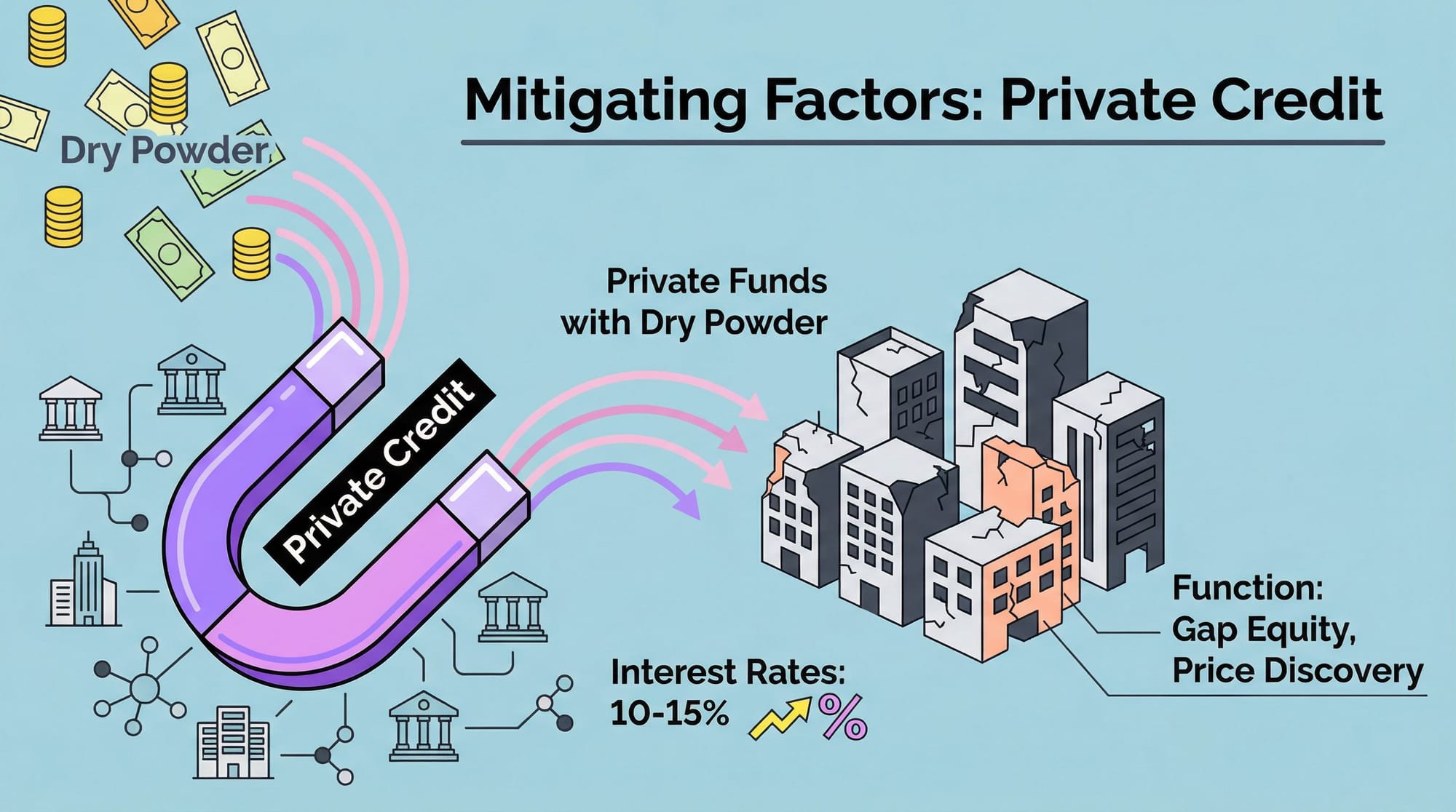

Private Credit's Role: Unlike 2008, there's a robust ecosystem of non-bank lenders with significant "dry powder". These private funds are stepping in to provide "gap equity" or mezzanine debt, preventing immediate liquidation, albeit at a high cost (10-15% interest). These opportunistic funds also acquire distressed assets, helping to establish a "floor" for valuations and facilitate price discovery.

The Great Digestion: A Prolonged Process, Not a Sudden Event

The strategic conclusion is clear: we are not facing a sudden "event" crisis but a prolonged "process" crisis – a slow-motion repricing of assets that will unfold over the remainder of the decade. The banking crisis will likely be contained to regional banks, leading to a period of consolidation as healthier institutions acquire weaker peers, often facilitated by the FDIC.

The most significant immediate impact will be a "credit crunch" for small businesses. As regional banks conserve capital to absorb potential CRE losses, they will reduce lending to other sectors, acting as a drag on economic growth.

This period, from 2024 to 2026, will be defined by "The Great Digestion":

- Banks will gradually work through distressed loans, booking losses quarter by quarter.

- Cities will undergo painful fiscal adjustments, forced to diversify revenue streams beyond commercial property taxes.

- Real estate will continue its K-shaped recovery. Trophy assets will thrive, while Class B and C office space will struggle, eventually being repurposed or demolished.

The "Urban Doom Loop" is a high-probability scenario for cities heavily reliant on legacy office markets, such as San Francisco, St. Louis, and downtown Los Angeles, which have not yet found their bottom. Conversely, cities with diversified economies and strong population growth, like Dallas, Miami, or even New York City, appear to be escaping this feedback loop, demonstrating a selective urban vibrancy.

"The 'maturity wall' of 2025 is not a cliff, but a steep hill. The banking system has been given the regulatory tools to climb it, slowly."

The climb will entail years of sub-par profitability for regional banks and a permanent resetting of the fiscal contract between major American cities and their commercial landlords. This isn't just about financial numbers; it's about the very fabric of our urban centers, the stability of our financial institutions, and the texture of our daily lives.

|  |  |