Decoding the Federal Reserve: Structure, Operations, and Impact

Unravel the mysteries of the Federal Reserve System. Explore its architecture, how it creates money, and its profound impact on your financial world, from its origins to modern policy.

|  |

Unveiling the Enigma: The Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve System, often mentioned in headlines concerning interest rates or inflation, remains a mystery to many despite its pervasive influence on our financial lives. This article aims to pull back the curtain, revealing the intricate architecture, operations, and the fascinating political economy of money as shaped by the Fed.

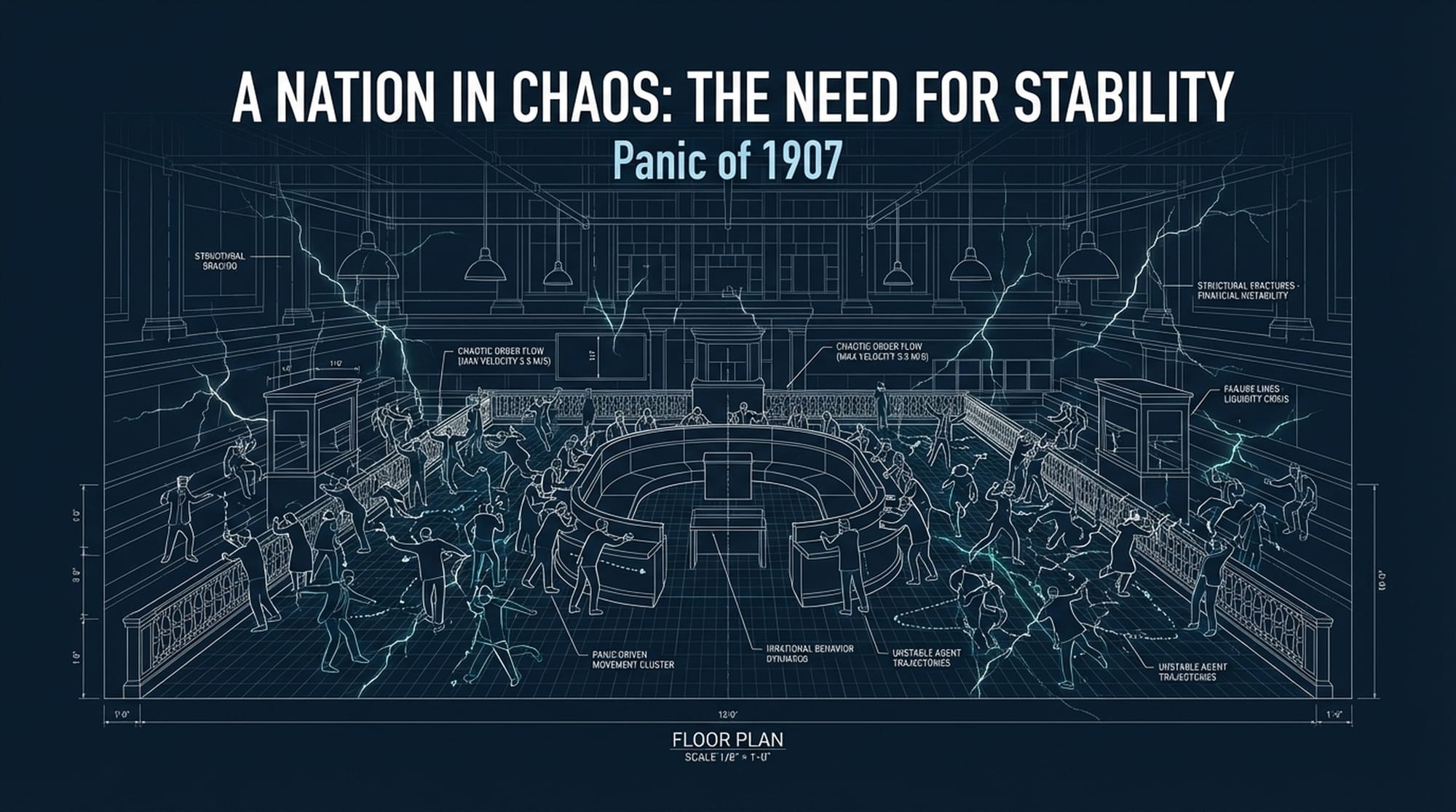

Born from Chaos: The Genesis of the Fed

The early twentieth century in the United States was a period marked by frequent and devastating financial panics. The most notable, the Panic of 1907, vividly exposed the nation's vulnerability due to the absence of a central authority capable of stabilizing the financial system or acting as a lender of last resort. It was a wild west of banking, prone to economic fear and instability.

Out of this chaos, in 1913, something revolutionary was born: The Federal Reserve System.

When President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act, he established a unique hybrid institution. It was a decentralized network designed to balance the often-conflicting interests of private commercial banks and the federal government, intended as a bulwark against future financial instability.

Independent Within Government: A Unique Autonomy

The Fed's structure is often described as independent within the government—a fundamental reality rather than mere rhetoric. While its authority stems from Congress and it is subject to legislative oversight, its monetary policy decisions remarkably do not require presidential approval, nor does it rely on congressional funding. This independence is paramount, designed to shield monetary policy from the short-term pressures of political cycles, allowing the Fed to focus on long-term economic stability.

Dispelling the Myth: Who Truly Owns the Fed?

A persistent myth suggests the Federal Reserve is a private entity owned by wealthy bankers. The truth is far more nuanced. The Fed comprises three main components: the Board of Governors in Washington D.C., twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks, and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The confusion often arises from the twelve regional Reserve Banks, which are structured like private corporations and issue shares to member commercial banks.

However, this is not ownership in the conventional sense. This stock cannot be sold, traded, or used as collateral; it is simply a legal requirement for banks to participate in the system. While member banks receive a statutory dividend on their paid-in capital, this rate is strictly regulated. Crucially, this stock conveys no claim on the Fed’s residual earnings. After expenses and minor dividends, every remaining dollar of the Reserve Banks' net earnings goes directly to the U.S. Treasury.

The ultimate economic beneficiary is the public purse. The Federal Reserve is a public institution, designed for public good.

The Fed's Architecture: A System of Checks and Balances

The Central Nerve Center: Board of Governors

At the core of the Fed, its central nervous system, is the Board of Governors in Washington D.C. This independent federal agency consists of seven members appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. To ensure their independence, they serve staggered fourteen-year terms, a design intended to prevent any single president from stacking the board with loyalists. This Board wields immense power, regulating the entire U.S. financial system, supervising regional Reserve Banks, and holding a permanent majority on the all-important FOMC.

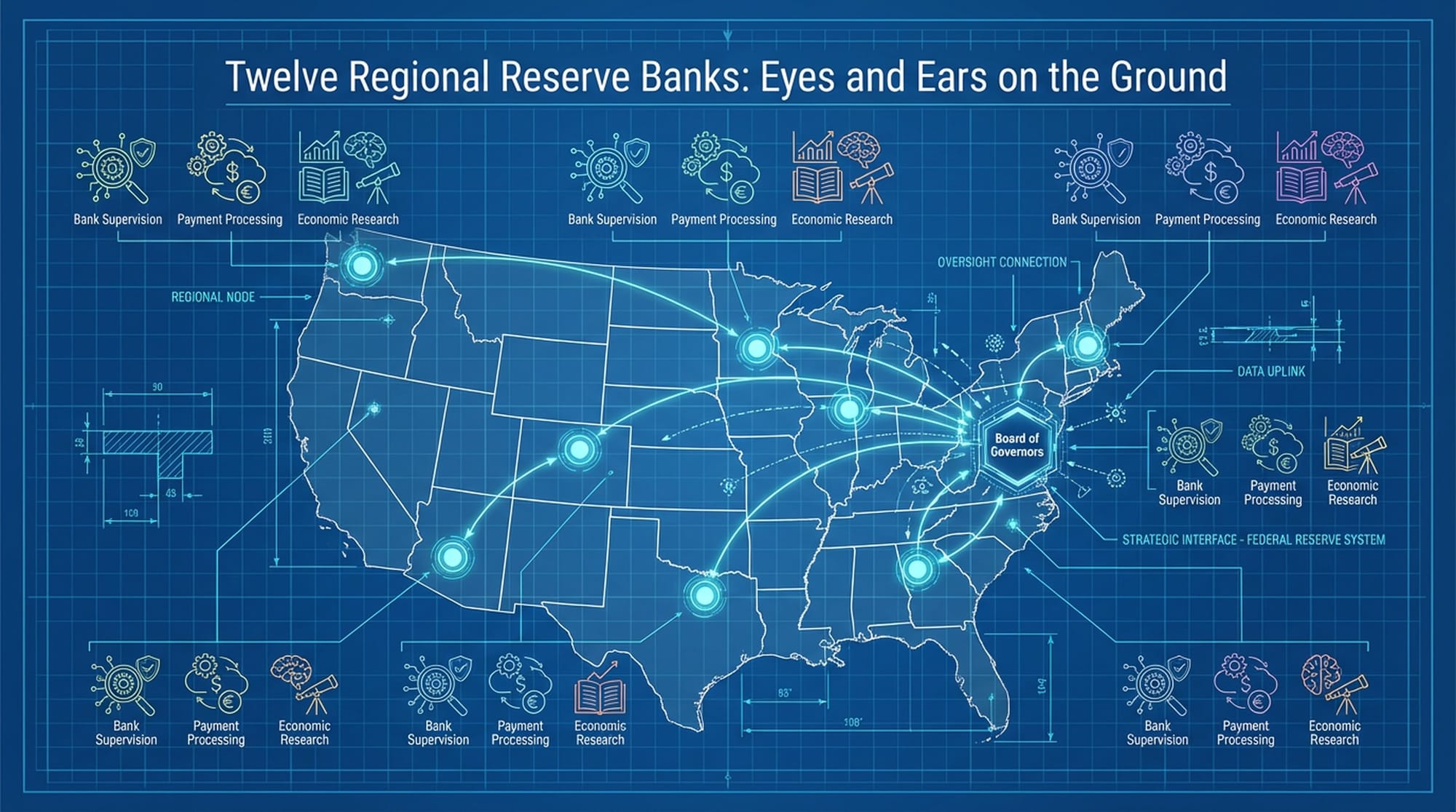

Eyes and Ears on the Ground: Regional Reserve Banks

The twelve regional Reserve Banks, spread across the country, act as the decentralized operating arms of the central bank. They distribute currency, supervise member banks, process payments, and conduct vital economic research tailored to their specific regions. They are the eyes and ears, gathering ground-level economic intelligence that informs national policy decisions.

Among these, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY) holds a unique first among equals status. Located in the financial capital, FRBNY is the only regional bank with a permanent voting seat on the FOMC and is responsible for executing monetary policy through its Open Market Trading Desk.

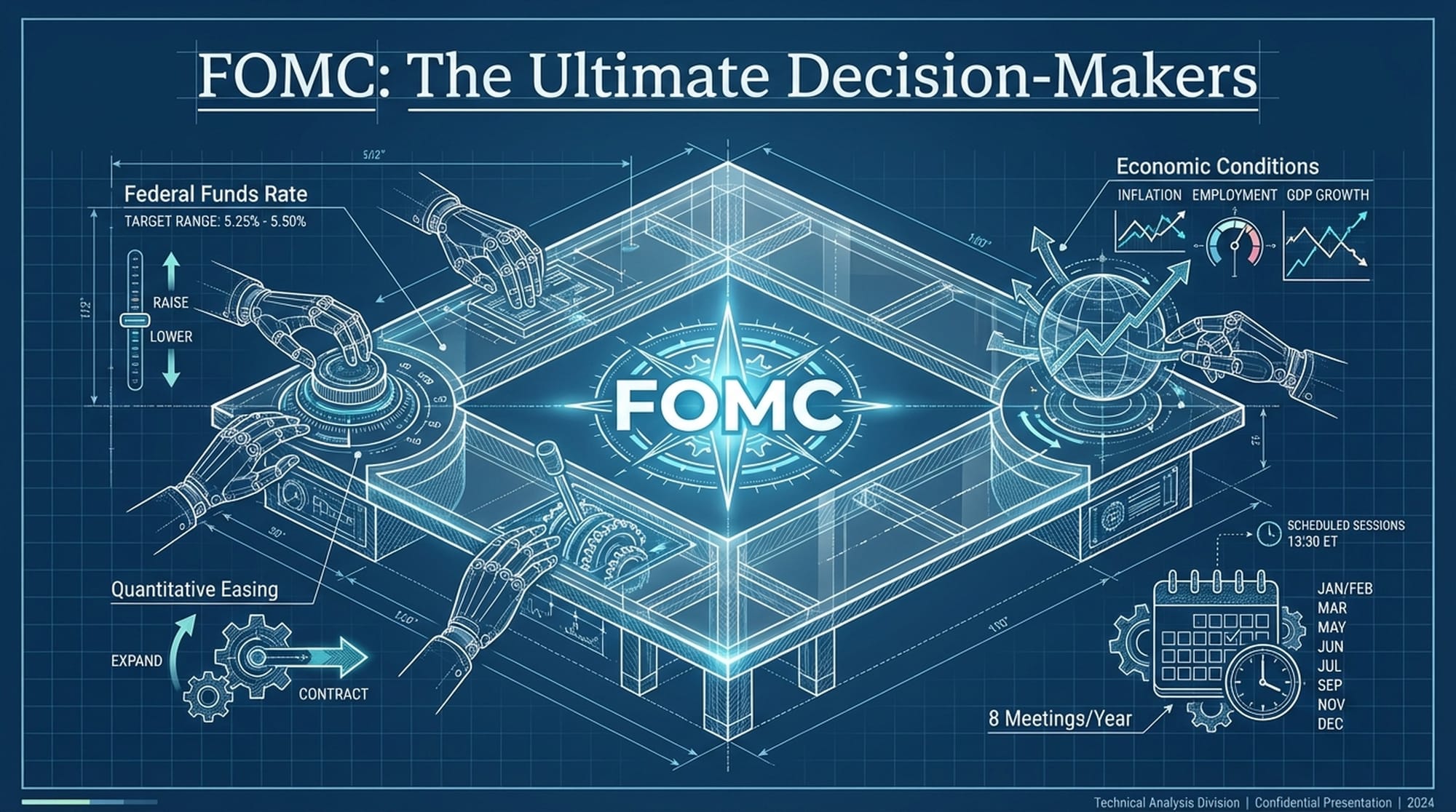

The Ultimate Decision-Makers: The FOMC

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) holds the ultimate decision-making power. This committee oversees open market operations—the buying and selling of government securities—which is the primary tool for influencing the nation's money supply. The FOMC meets eight times a year to assess economic conditions and set the target range for the federal funds rate, a rate that impacts nearly every loan and investment in the country.

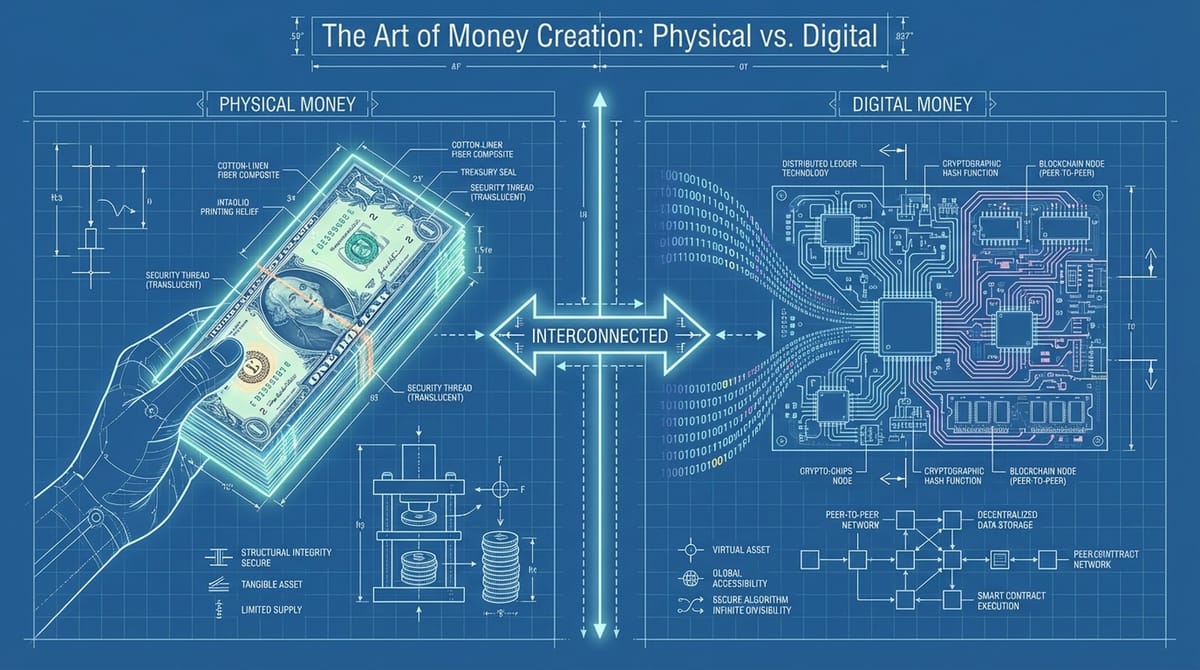

The Art of Money Creation: Physical vs. Digital

Understanding money creation requires distinguishing between physical currency and digital reserves.

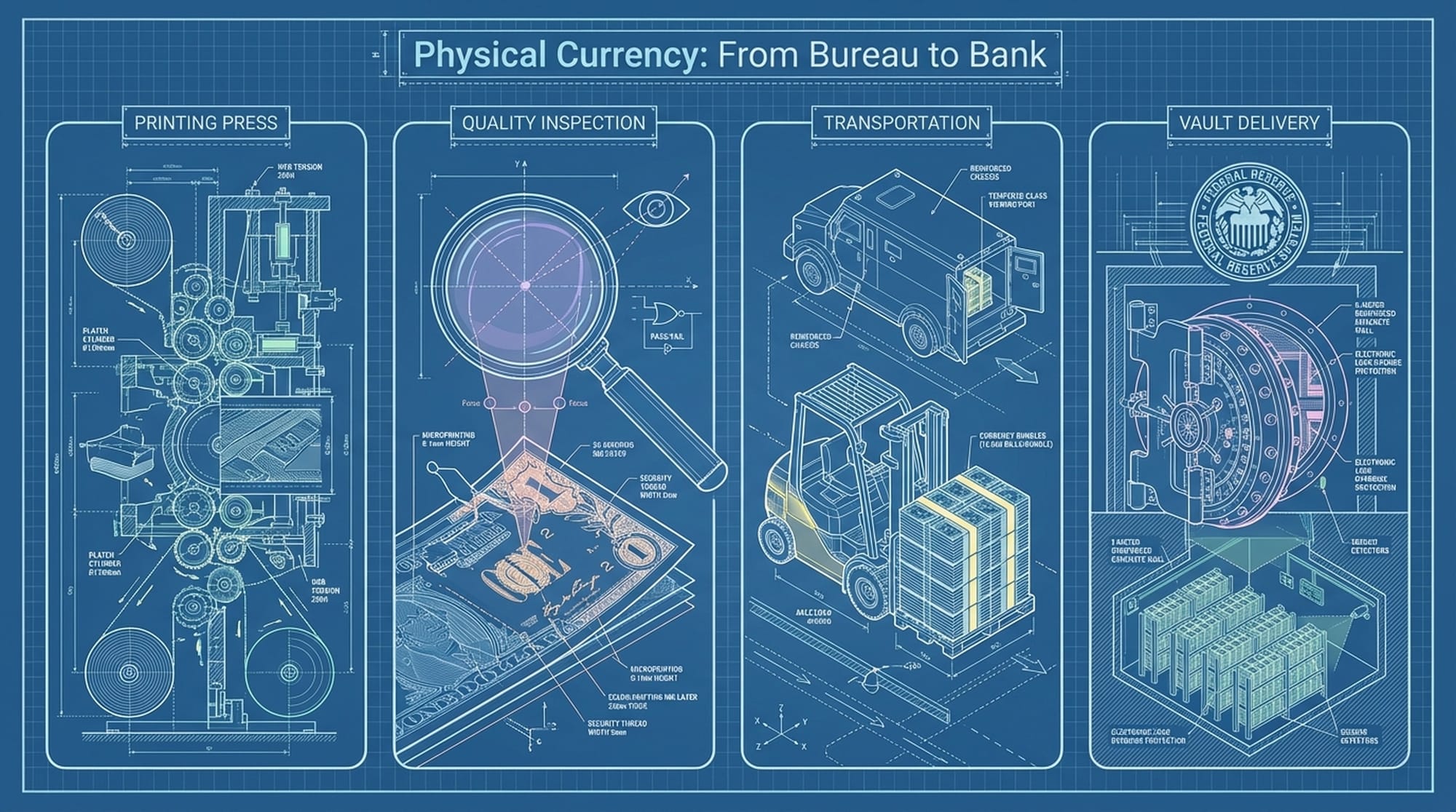

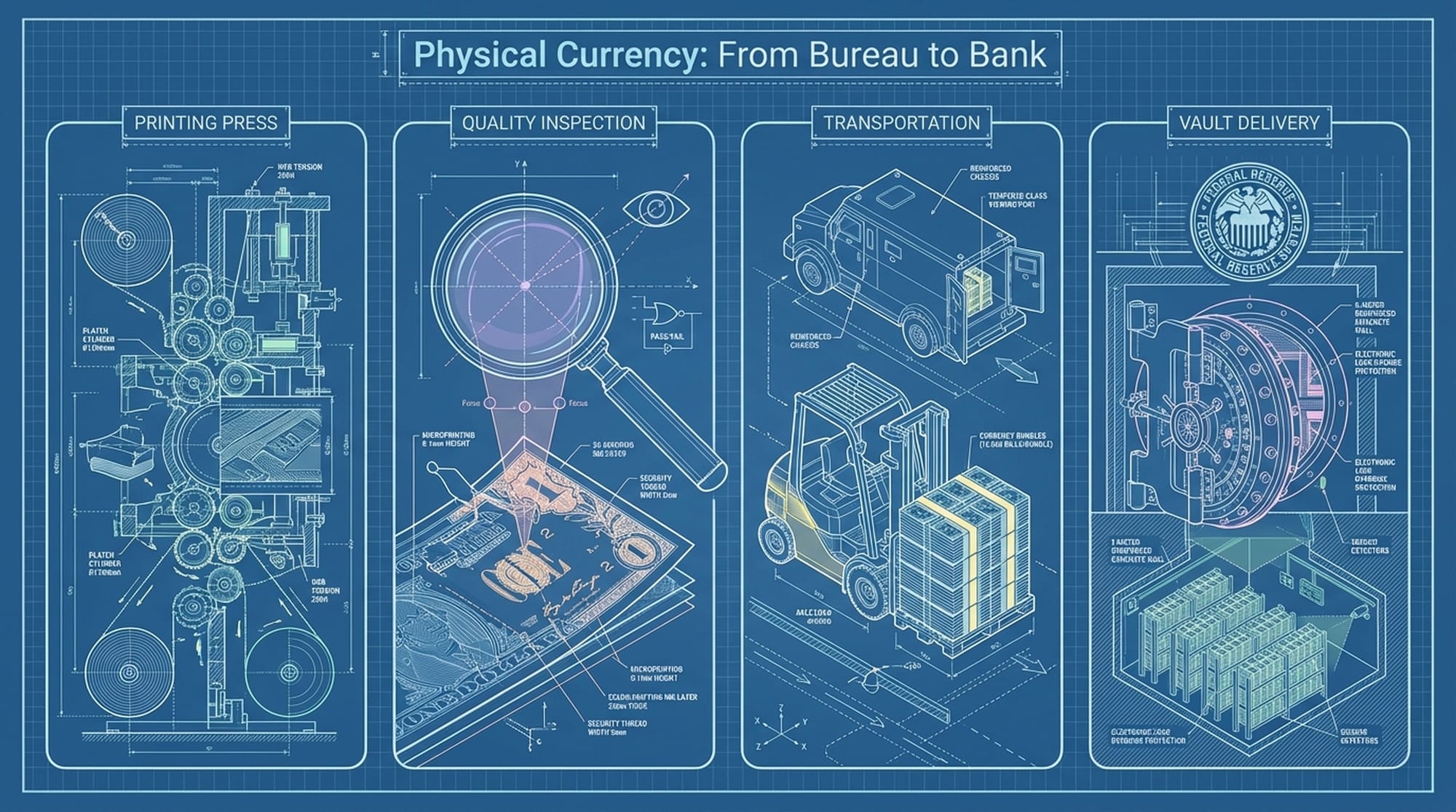

Physical Currency: From Bureau to Bank

Contrary to popular belief, the Federal Reserve does not physically print money. That is the responsibility of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, a division of the U.S. Department of the Treasury. The Fed acts as the customer and distributor. The production of U.S. currency is a high-security industrial operation, involving specialized paper and intricate printing processes. Each year, the Fed projects demand for new currency and places an order. These notes, once printed, become liabilities of the Federal Reserve Banks, distributed to commercial banks as needed.

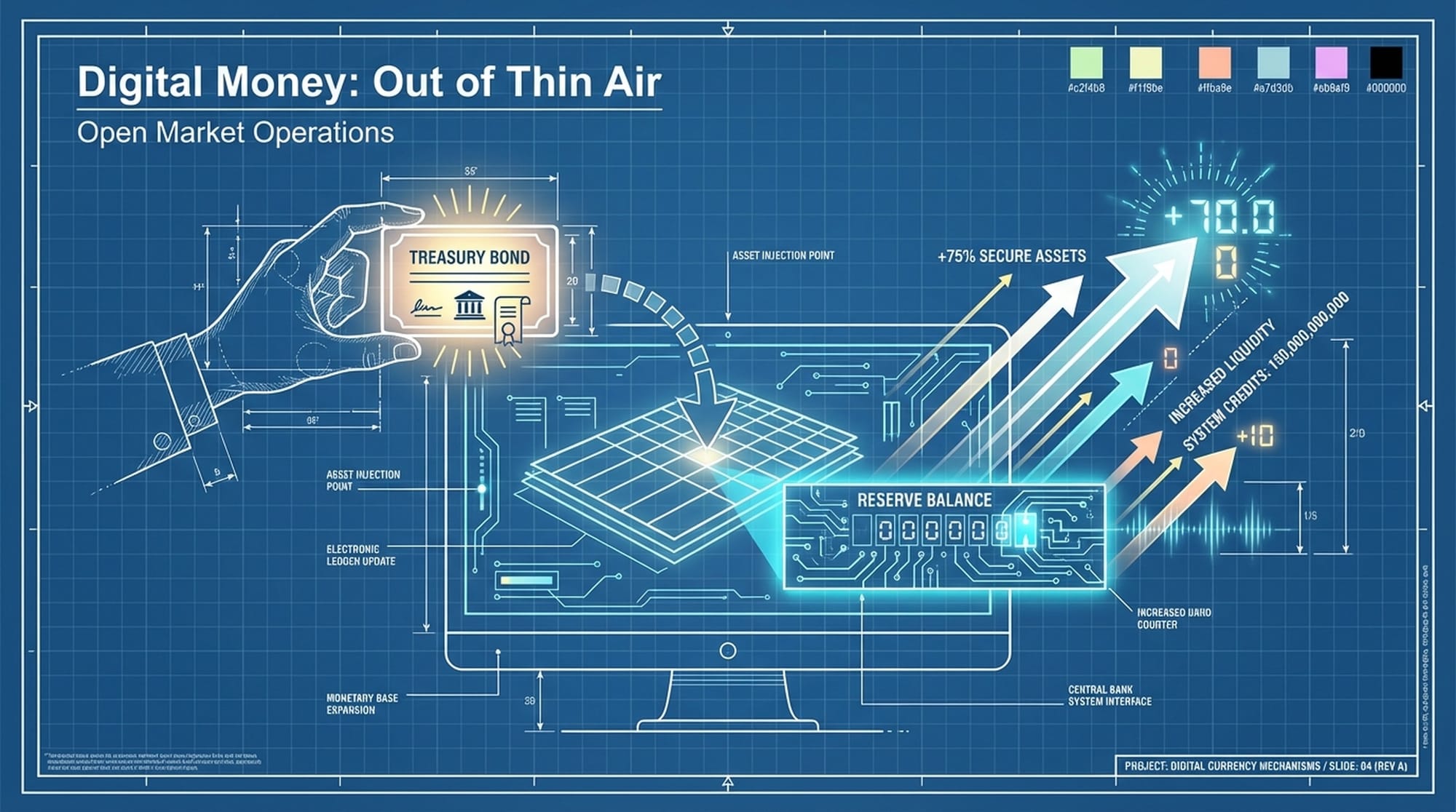

Digital Money: Out of Thin Air

The vast majority of our money supply exists as digital entries on the Federal Reserve’s ledger. The Fed creates this money out of thin air through its balance sheet operations, primarily via Open Market Operations. When the Fed purchases a security, such as a Treasury bond, from a private entity, it pays by crediting the seller's bank with reserve balances. These new reserves are created in the act of purchase. Conversely, when the Fed sells a security, it debits the buyer's reserve account, effectively extinguishing that money from the system.

Debunking the 'Money Multiplier' Myth

The traditional money multiplier concept, where banks mechanically multiply reserves into loans, is largely obsolete. Post-2008, and especially since 2020 with reserve requirements set to zero, this mechanical link has been severed. Banks do not lend simply because they have excess reserves; they lend based on the availability of creditworthy borrowers and profitable investment opportunities. In today’s ample reserves regime, the real constraints on lending are capital requirements and banks’ risk appetites, not the quantity of reserves.

Crisis as Catalyst: The Fed's Evolution

The modern Federal Reserve is largely defined by its responses to historical crises, each profoundly reshaping its toolkit and philosophy.

- The Great Depression (1929-1933): The Fed's failure during this period, marked by a fragmented structure and a refusal to expand the money supply, led to the collapse of the money supply and widespread bank failures. This catastrophe spurred the Banking Act of 1935, centralizing power in the Board of Governors.

- The Volcker Shock (1979): Facing spiraling inflation, Chairman Paul Volcker implemented a radical shift, targeting the quantity of money rather than interest rates. This led to a sharp rise in the federal funds rate (to 20% in 1980) and a severe recession, but ultimately broke inflation and ushered in the

Great Moderation. - 2008 Financial Crisis & COVID-19 Pandemic: These crises forced the Fed to expand its toolkit beyond traditional banking. In 2008, the Fed became a

lender of last resort for non-banksby creating emergency facilities to backstop the commercial paper market. During the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, facing a liquidity freeze in the U.S. Treasury market, the Fed responded withunlimited QE, buying nearly a trillion dollars in securities to restore market functioning, signaling its role as a market maker of last resort.

The Enduring Evolution of the Federal Reserve

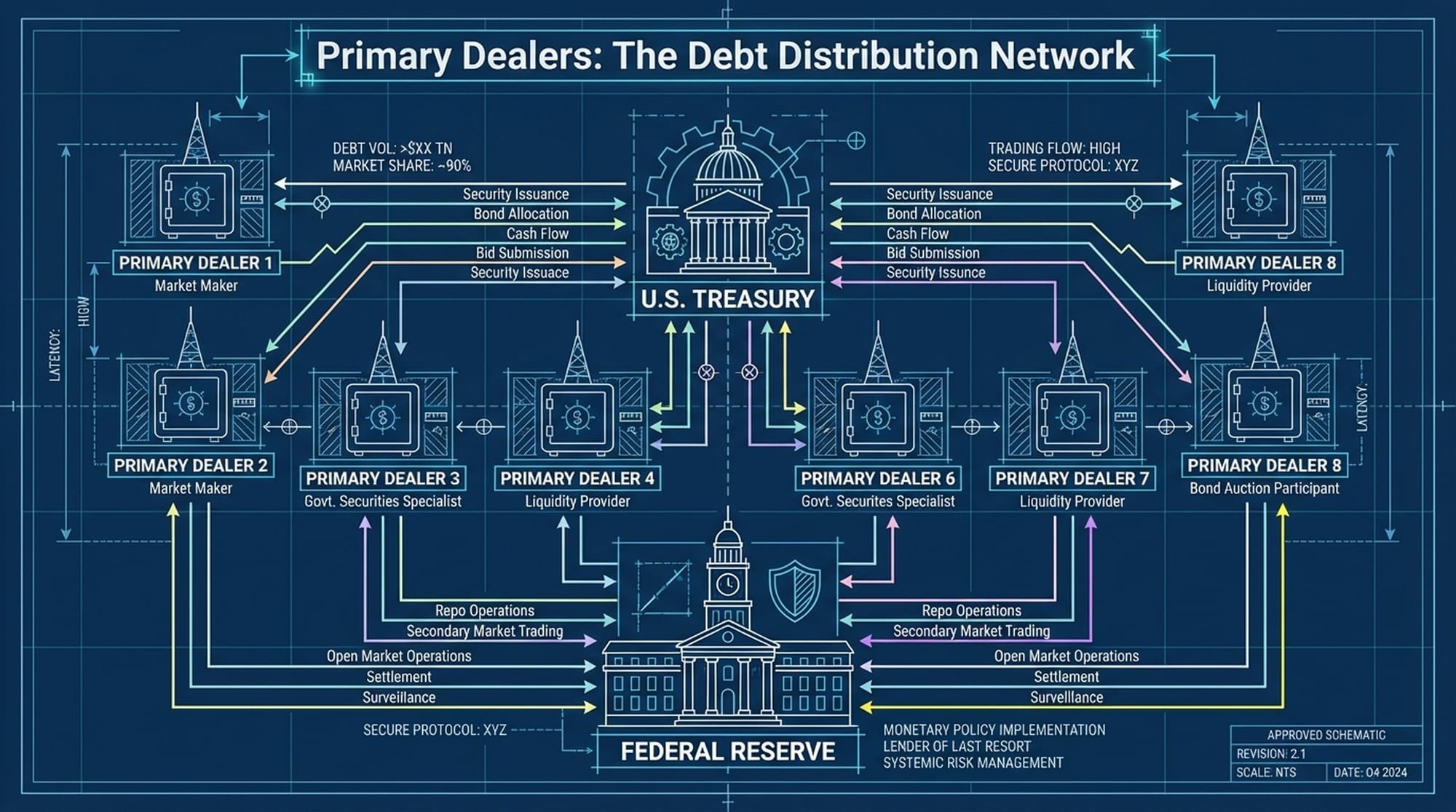

The Federal Reserve System has evolved significantly from its origins as a decentralized backstop for commercial banks into the preeminent manager of the global financial cycle. Through complex mechanisms like the Ample Reserves framework, symbiotic debt monetization with Primary Dealers, and the blunt force of Quantitative Easing, the Fed exerts profound gravity on the economy.

Its history is a continuous saga of reactive adaptation. From the tragic passivity of the Great Depression to the aggressive, unprecedented interventionism of 2008 and 2020, the Fed has constantly redefined the boundaries of central banking. Today, it stands as a market maker of last resort, possessing the theoretical power to create infinite liquidity. However, this power is constrained by the practical realities of inflation and its fundamental mandate to maintain the purchasing power of the currency it issues.

Understanding the Fed requires navigating this duality: it is a technician of the highest order, managing basis points and settlement cycles with precision, yet it remains, at its core, a political institution. Its decisions are not just economic; they are profoundly political, managing the distribution of pain and prosperity in the American economy. Its future, and ours, remains intricately linked to its capacity to adapt, learn, and navigate the complexities of an ever-changing global financial landscape.

|  |